Introduction

The world is reorganizing. People are attempting to comprehend the implications of recent events across a variety of dimensions: politically, geopolitically, economically, financially and socially. A feeling of uncertainty has eclipsed global affairs and individuals are developing an increased reliance on the thoughts of those bold enough to attempt comprehension. Experts are everywhere, but the expert is nowhere.

I am not claiming to be an expert on anything, either. I read, write and do my best to piece together an understanding of vague and complex concepts. I’ve spent some time reading and thinking through various concepts and believe we are witnessing an inflection point of global trust.

My goal is to explain the framework that led me to this conclusion. I’ll generally avoid discussing geopolitics and focus on the monetary and financial implications of this shift we are witnessing. The best place to start is understanding trust.

The World Runs On Trust

We are witnessing a shift in global trust, setting the table for a new global monetary order. Consider Antal Fekete’s introduction from his seminal work Whither Gold?:

“The year 1971 was a milestone in the history of money and credit. Previously, in the world's most developed countries, money (and hence credit) was tied to a positive value: the value of a well-defined quantity of a good of well-defined quality. In 1971 this tie was cut. Ever since, money has been tied not to positive but to negative values -- the value of debt instruments.”

Debt instruments (credit) are built on trust — the most fundamental construct of organization. Organization allowed humanity to genetically eclipse its ancestors. Relationships, whether between individuals or groups, hinge on trust. Societies developed technologies and social structures to reduce the need for trust through reputations, security and money.

Reputations reduce the need to trust because they represent an individual’s pattern of behavior: You trust some people more than others because of how they’ve acted in the past.

Security reduces the need to trust that others will not hurt you in some form. You build a fence because you don’t trust your neighbors. You lock your car because you don’t trust your community. Your government has a military because it doesn’t trust other governments. Security is the price you pay to avoid the costs of vulnerability.

Money reduces the need to trust that an individual will return a favor to you in the future. When you provide an individual a good or service, rather than trusting that they will return it to you in the future, they can immediately trade money to you, eliminating the need to trust. Stated differently, money reduces the need to trust that positive outcomes will happen while reputations and security reduces the need to trust that negative outcomes won’t happen. When money became entirely unanchored from gold in 1971, the value of money became a function of reputations and security, requiring trust. Before then, money was tied to the commodity gold, which maintained value through its well-defined quality and well-defined quantity and therefore didn’t require trust.

Trust at a global level appears to be shifting across reputations and security, and thus credit money:

- Reputations — countries are trusting each other’s reputations less. The U.S. government’s reputation throughout recent history has been a global pillar of political stability and standard of financial and economic prudency. This is changing. The rise of U.S. populism has hindered its reputation as a politically stable country that allies depend on and rivals fear. Unprecedented economic and financial policy measures (e.g., bailouts, deficit spending, monetary inflation, debt issuance, etc.) are causing international powers to question the stability of the U.S. financial system. A hindrance to the reputation of the U.S. is a hindrance on the value of its money, to be discussed below.

- Security — countries are witnessing a contraction in global military order. The U.S. has been reducing its military presence and the world is shifting from a unipolar to a multipolar structure of order. The U.S.’ withdrawal of its military presence abroad has reduced its role as the monitor of international order and given rise to the military presence of rival nations. Reducing the assurance of its military presence internationally reduces the value of the dollar.

- Money — countries are losing trust in the international monetary order. Money has existed as either a commodity or credit (debt). Commodity money is not subject to trust through the reputations and security of governments while credit money is. Our modern system is entirely credit-based and the credit of the U.S. is the pillar upon which it exists. If the global reserve currency is based on credit, then the reputation and security of the U.S. is paramount to maintaining international monetary order. Trust in political and financial stability impacts the value of the dollar as does its holders’ demand for liquidity and stability. However, it’s not just U.S. credit money that is losing trust; it’s all credit money. As political and financial stability decline, we are witnessing a shift away from credit money entirely, incentivizing the adoption of commodity money.

U.S. Debt Is Not Risk Free

Most recently, the reputation of U.S. credit has declined in an unprecedented way. Foreign governments historically trusted that the U.S. government’s debt is risk free. When financial sanctions froze Russia’s foreign exchange reserves, the U.S. undermined this risk-free reputation, as even reserves are now subject to confiscation. The ability to freeze the reserve assets of another country removed a foreign government’s right to either repay its debts or spend those assets. Now, international observers are realizing that these debts are not risk free. As the debt of the U.S. government is what backs its currency, this is a significant cause for concern.

When the U.S. government issues debt, and demand from domestic and foreign buyers of it isn’t strong enough, the Federal Reserve prints money to purchase it in the open market and generate demand. Thus, the more U.S. debt countries are willing to buy, the stronger the U.S. dollar becomes — requiring less money printing by the Fed to indirectly enable government spending. Trust in the U.S. government’s credit has now been damaged, and thus so has the credit of the dollar. Further, trust in credit is declining in general, leaving commodity money as the more trustless option.

First, I will examine this shift in the U.S. which applies specifically to its reputation and security, and then discuss the shifts in global credit (money).

U.S. Dollar Dominance

Will foreign governments attempt to de-dollarize? This question is complex as it not only requires an understanding of the global banking and payment systems but also maintains a geopolitical background. Countries around the world, both allies and rivals, have strong incentives to end global dollar hegemony. By utilizing the dollar a country is subject to the purview of the U.S. government and its financial institutions and infrastructure. To better understand this, let’s start by defining money:

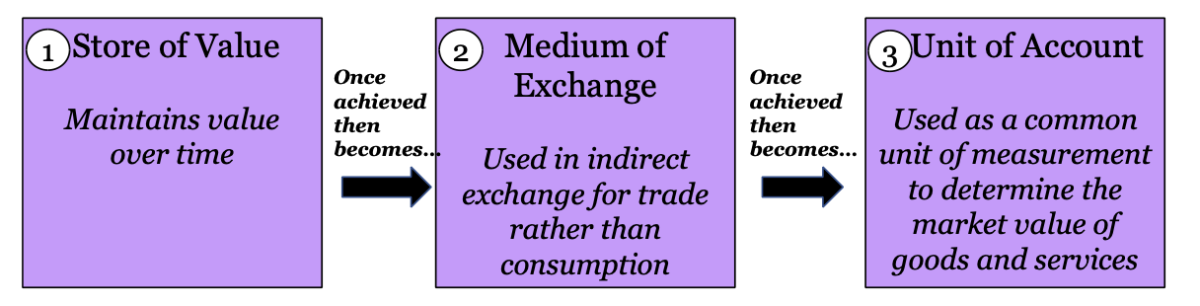

The above figure from my book shows the three functions of money as a store of value, medium of exchange and unit of account, as well as the supporting monetary properties of each below them. Each function plays a role in international financial markets:

- Store of Value — fulfilling this function drives reserve currency status. U.S. currency and debt is ~60% of global foreign reserves. A country will denominate its foreign exchange reserve assets in the most creditworthy assets — defined by their stability and liquidity.

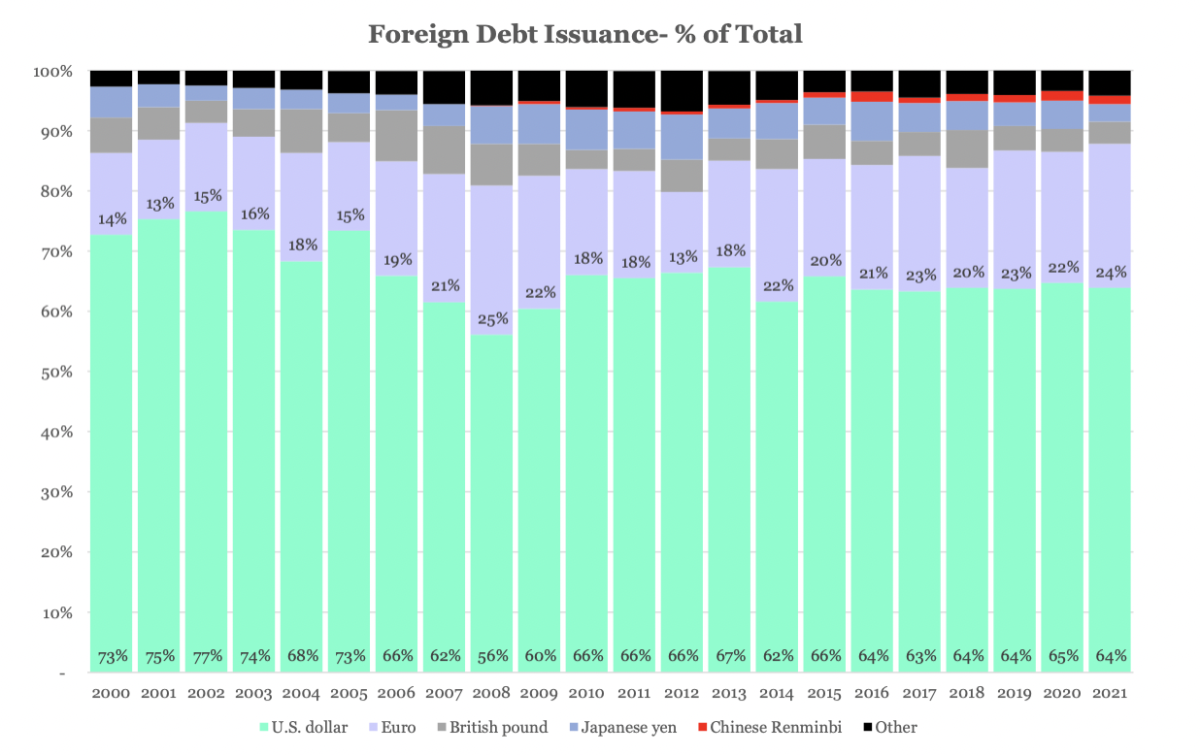

- Medium of Exchange — this function is closely tied to being a unit of account. The dollar is the dominant invoicing currency in international trade and the euro is a close second, both of which fluctuate around ~40% of total. The dollar is also 64% of foreign currency debt issuance, meaning countries mostly denominate their debt in dollars. This creates demand for the dollar and is important. Since the U.S. issues more debt than domestic and foreign buyers are naturally willing to buy, they must print dollars to buy it in the market, which is inflationary (all else equal). The more foreign demand they can create for these newly printed dollars, the lower the inflationary impact from printing new dollars. This foreign demand becomes entrenched as countries denominate their contracts in the dollar, allowing the U.S. to monetize their debt.

- Unit of Account — Oil and other commodity contracts are often denominated in U.S. dollars (e.g., the petrodollar system). This creates artificial demand for the dollar, supporting its value while the U.S. government continually issues debt beyond amounts domestic and foreign buyers would be willing to purchase without the Fed creating demand for it. The petrodollar system was created by Nixon in response to a multi-year depreciation of the dollar after its fixed convertibility into gold was removed in 1971. In 1973, Nixon struck a deal with Saudi Arabia in which every barrel of oil purchased from the Saudis would be denominated in the U.S. dollar and in exchange, the U.S. would offer them military protection. By 1975, all OPEC nations agreed to price their own oil supplies in dollars in exchange for military protection. This system spurred artificial demand for the dollar and its value was now tied to demand for energy (oil). This effectively entrenched the U.S. dollar as a global unit of account, allowing it more leeway in its practices of money printing to generate demand for its debt. For example, you may not like that the U.S. is continually increasing its deficit spending (hindering its store of value function), but your trade contracts require you to use the dollar (supporting its medium of exchange and unit of account function), so you have to use dollars anyway. Put simply, if foreign governments won’t buy U.S. debt, then the U.S. government will print money to buy it from itself and contracts require foreign governments to use that newly printed money. In this sense, when the U.S. government’s creditworthiness (reputation) falls short, its military capabilities (security) pick up the slack. The U.S. trades military protection for increased foreign dollar demand, enabling it to continuously run a deficit.

Let’s summarize. Since its establishment, the dollar has served the functions of money best at an international level because it can be easily traded in global markets (i.e., it’s liquid), and contracts are denominated in it (e.g., trade and debt contracts). As U.S. capital markets are the broadest, most liquid and maintain a track record of secure property rights (i.e., strong reputation), it makes sense that countries would utilize it because there is a relatively lower risk of significant upheaval in U.S. capital markets. Contrast this idea with the Chinese renminbi which has struggled to gain dominance as a global store of value, medium of exchange and unit of account due to the political uncertainty of its government (i.e., poor reputation) which maintains capital controls on foreign exchange markets and frequently intervenes to manipulate its price. U.S. foreign intervention is rare. Further, having a strong military presence enforces dollar demand for commodity trade per agreements with foreign countries. Countries that denominate contracts in dollars would need to be comfortable trading away military security from the U.S. to buck this trend. With belligerent Eastern leaders increasing their expanse, this security need is considerable.

Let’s look at how the functions of money are enabled by a country’s reputation and security:

- Reputation: primarily enables the store of value function of its currency. Specifically, countries that maintain political and economic stability, and relatively free capital markets, develop a reputation for safety that backs their currency. This safety can also be thought of as creditworthiness.

- Security: primarily enables the medium of exchange and unit of account functions of its currency. Widespread contract denomination and deep liquidity of a currency entrench its demand in global markets. Military power is what entrenches this demand in the first place.

If the reputation of the U.S. declines and its military power withdraws, demand for its currency decreases as well. With the shifts in these two variables in front of mind, let’s consider how demand for the dollar could be affected.

Overview Of The Global Monetary System

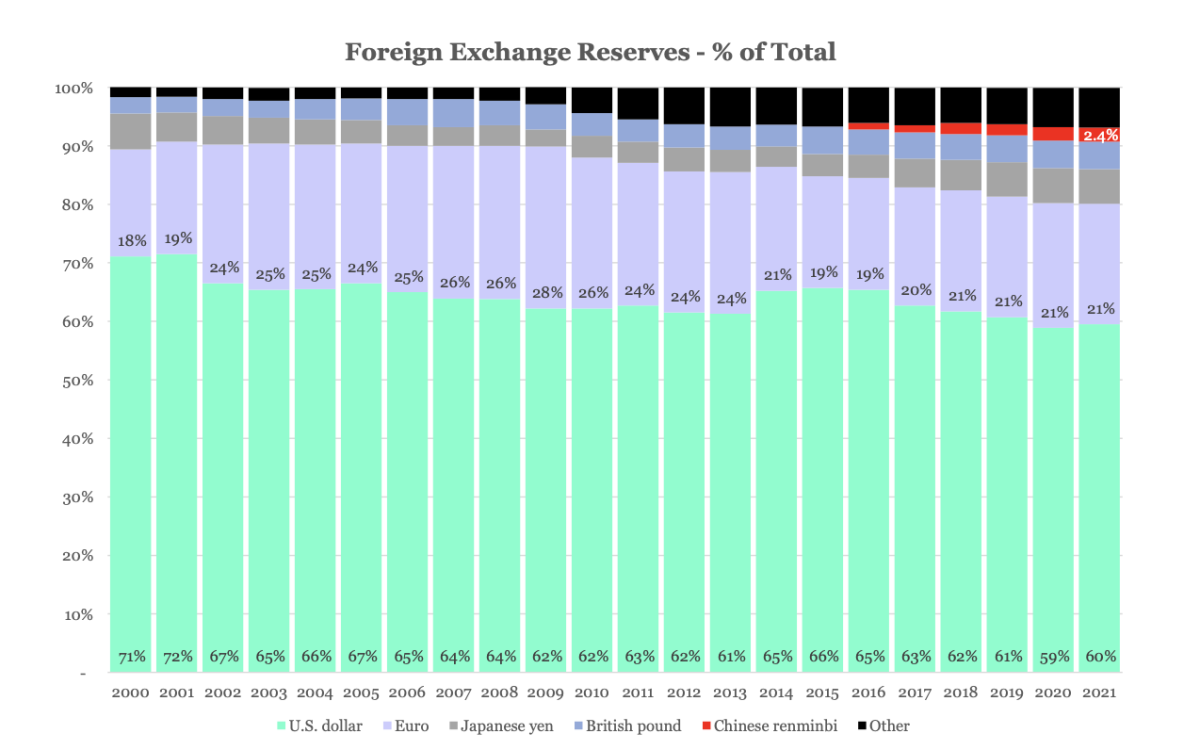

Global liquidity and contract denomination can be measured by analyzing foreign reserves, foreign debt issuance, and foreign transactions/volume. Dollar foreign exchange reserves gradually declined from 71% to 60% since the year 2000. Three percent of the decline is accounted for in the euro, 2% from the pound, 2% from the renminbi and the remaining 4% from other currencies.

More than half of the 11 percentage point decline has come from China and other economies (e.g., Australian dollars, Canadian dollars, Swiss francs, et al.). While the U.S. dollar decline in dominance is material, it obviously remains dominant. The primary takeaway is that most of the decline in dollar dominance is being captured by smaller currencies, indicating that global reserves are gradually becoming more dispersed. Note that this data should be interpreted with caution as the fall in dollar dominance since 2016 occurred when previous non-reporting countries (e.g., China) began gradually revealing their FX reserves to the IMF. Further, governments don’t have to be honest about the numbers they report — the politically sensitive nature of this information makes it ripe for manipulation.

Source: IMF

Foreign debt issuance in USD (other countries borrowing in contracts denominated in dollars) has also gradually declined by ~9% since 2000, while the euro has gained ~10%. Debt issuance of the remaining economies was relatively flat over this period so most of the change in dollar debt issued can be attributed to the euro.

Source: Federal Reserve

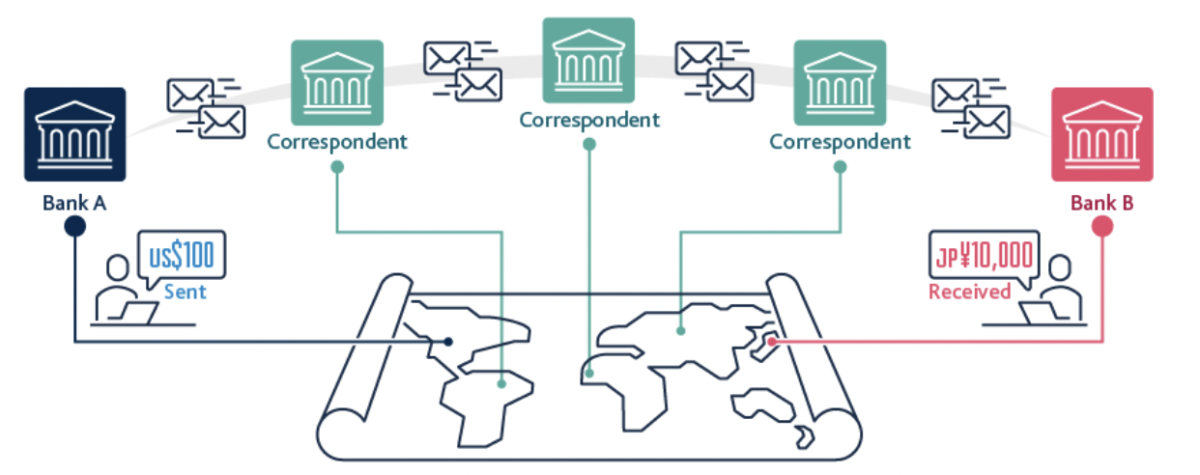

The currency composition of foreign transactions is interesting. Historically, globalization has increased the demand for cross-border payments primarily due to:

- Manufacturers expanding supply chains across borders.

- Cross-border asset management.

- International trade.

- International remittances (e.g., migrants sending money home).

This poses a problem for smaller economies: the more intermediaries that are involved in cross-border transactions, the slower and more expensive these payments become. High-volume currencies, such as the dollar, have a shorter chain of intermediaries while lower-volume currencies (e.g., emerging markets) have a longer chain of intermediaries. This is important because it is these emerging markets that stand to lose the most from international payments and for this reason alternative systems are attractive to them.

Source: Bank of England

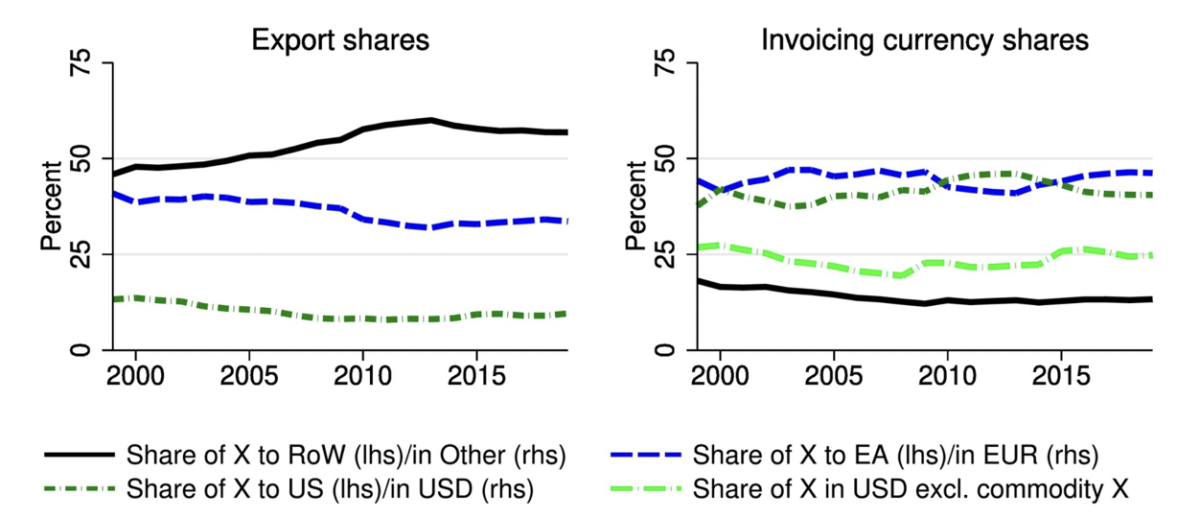

If we look at the trend in composition of foreign payments it’s evident that the dollar's share of invoicing is materially greater than its share of exports, illuminating its outsized role of invoicing in proportion to trade. The euro has been competing with the dollar in terms of invoicing share, but this is driven by its usage for export trade among EU countries. For the rest of the world, export share has been, on average, greater than 50% while invoicing share has remained less than 20% on average.

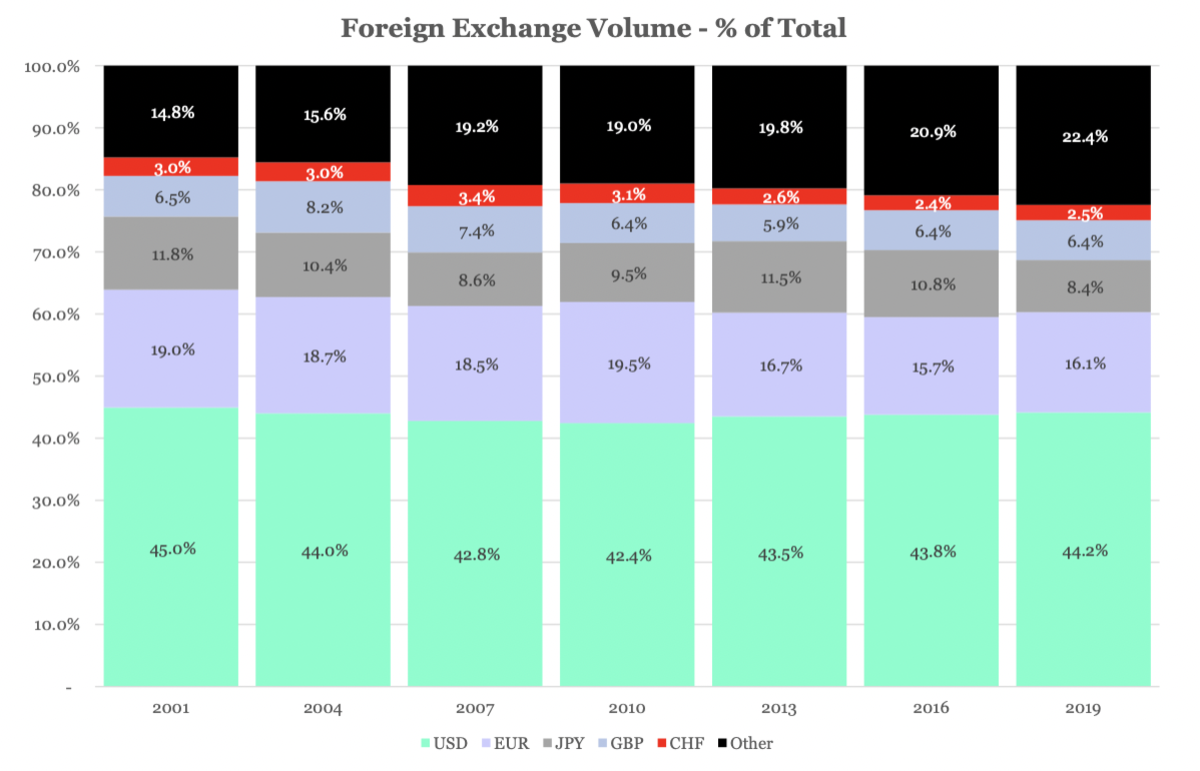

Lastly, let’s discuss the volume of trade. A currency with high volume of trade means that it is relatively more liquid and thus, more attractive as a trade vehicle. The chart below shows the proportions of volume traded by currency. The dollar has remained dominant and constant since 2000, expressing its desirability as a liquid global currency. What’s important is that the volume of all major global reserve currencies have declined slightly while the volume of “other” smaller world currencies has increased from 15% to 22% in proportion.

Source: BIS Triennial Survey; (Note: typically these numbers are shown on a 200% scale — e.g., for 2019 USD would be 88.4% out of 200% — because there are two legs to every foreign exchange trade. I’ve condensed this to a 100% scale for ease of interpretation of the proportions).

The dollar is dominant across every metric, although it has been gradually declining. Most notably, economies that are not major world reserves are:

- Gaining dominance as reserves and thus world FX reserves are becoming more dispersed.

- Utilizing the dollar for foreign transactions in significantly greater proportions than their exports and limited by a long chain of intermediaries when attempting to use their domestic currencies.

- Hurt the most by long chains of global intermediaries for their transactions and thus stand to gain the most from alternative systems.

- Increasing their share of foreign exchange volume (liquidity) while all the major reserve currencies are declining.

There exists a trend whereby the smaller and less dominant currencies of the world are expanding but are still limited by dollar dominance. Pair this trend with the global political fragmentation occurring and their continued expansion becomes more plausible. As the U.S. withdraws its military power globally, which backs the dollar’s functions as a medium of exchange and unit of account, it decreases demand for its currency to serve these functions. Further, the dollar’s creditworthiness has declined since implementing the Russian sanctions. The trends of declining U.S. military presence and creditworthiness, as well as increased global fragmentation, indicate that the global monetary regime could experience drastic change in the near term.

The Global Monetary System Is Shifting

Russia invaded Ukraine on Feb. 24, 2022, and the U.S. subsequently implemented a swath of economic and financial sanctions. I believe history will look back on this event as the initial catalyst of change towards a new era of global monetary order. Three global realizations subsequently occurred:

Realization #1: Economic sanctions placed on Russia signaled to the world that US sovereign assets are not risk free. U.S. control over the global monetary system subjects all participating nations to the authority of the U.S.

Effectively, ~$300 billion of Russia’s ~$640 billion in foreign exchange reserves were “frozen” (no longer spendable) and it was partially banned (energy still allowed) from the SWIFT international payments system. However, Russia had been de-dollarizing and building up alternative reserves as protection from sanctions throughout previous years.

Now Russia is looking for alternatives, China being the obvious partner, but India, Brazil and Argentina are also discussing cooperation. Economic sanctions of this magnitude by the West are unprecedented. This has signaled to countries around the world the risk they run through dependence on the dollar. This doesn’t mean that these countries will begin cooperating as they are all subject to constraints under an international spiderweb of trade and financial relationships.

For example, Marko Papic explains in “Geopolitical Alpha” how China is heavily constrained by the satisfaction of its growing middle class (the majority of its population) and fearful that they could fall into the middle-income trap (GDP per capita stalling within the $1,000-12,000 range). Their debt cycle has peaked and economically they are in a vulnerable position. Chinese leaders understand that the middle-income trap has historically brought the death of communist regimes. This is where the U.S. has leverage over China. Economic and financial sanctions targeting this demographic can prevent growth in productivity and that is what China is most afraid of. Just because China wants to partner with Russia and achieve “world domination” does not mean that they will do so since they are subject to constraints.

The most important aspect of this realization is that U.S. dollar assets are not risk free: they maintain a risk of appropriation by the U.S. government. Countries with plans to act out of accordance with U.S. interests will likely start de-dollarizing before doing so. However, as much as countries would prefer to opt out of this dollar dependency, they are constrained in doing so as well.

Realization #2: It’s not just the U.S. that has economic power over reserves, it’s fiat reserve nations in general. Owning fiat currencies and assets in reserves creates uncertain political risks, increasing the desirability of commodities as reserve assets.

Let’s talk about commodity money vs. debt (fiat) money. In his recent paper, Zoltan Pozsar describes how the death of the dollar system has arrived. Russia is a major global commodity exporter and the sanctions have bifurcated the value of their commodities. Similar to subprime mortgages in the 2008 financial crisis, Russian commodities have become “subprime” commodities. They’ve subsequently declined materially in value as much of the world is no longer buying them. Non-Russian commodities are increasing in value as anti-Russia countries are now all purchasing them while the global supply has shrunk materially. This has created volatility in commodity markets, markets that have been (apparently) neglected by financial system risk monitors. Commodity traders often borrow money from exchanges to place their trades, with the underlying commodities as collateral. If the price of the underlying commodity moves too much in the wrong direction, the exchanges tell them that they need to pay more collateral to back their borrowed money (trader get margin-called). Now, traders take both sides in these markets (they bet the price will go up or that it will go down) and therefore, regardless of which direction the price moves, somebody is getting margin-called. This means that as price volatility is introduced to the system, traders need to pay more money to the exchange as collateral. What if the traders don’t have more money to give as collateral? Then the exchange has to cover it. What if the exchanges can’t cover it? Then we have a major credit contraction in the commodity markets on our hands as people start pulling money out of the system. This could lead to large bankruptcies within a core segment of the global financial system.

In the fiat world, credit contractions are always backstopped — such as the Fed printing money to bail out the financial system in 2008. What is unique to this situation is that the “subprime” collateral of Russian commodities is what Western central banks would need to step in and buy — but they can’t because their governments are the ones who prevented buying it in the first place. So, who is going to buy it? China.

China could print money and effectively bail out the Russian commodity market. If so, China would strengthen its balance sheet with commodities which would strengthen its monetary position as a store of value, all else equal. The Chinese renminbi (also called the “yuan”) would also begin spreading more widely as a global medium of exchange as countries that want to participate in this discounted commodity trade utilize the yuan in doing so. People are referring to this as the growth of the “petroyuan” or “euroyuan” (like the petrodollar and eurodollar, just the yuan). China is also in discussions with Saudi Arabia to denominate oil sales in the yuan. As China is the largest importer of Saudi oil, it makes sense that the Saudis would consider denominating trade in its currency. Further, the lack of U.S. military support for the Saudis in Yemen is all the more reason to switch to dollar alternatives. However, the more the Saudis denominate oil in contracts other than the dollar, the more they risk losing U.S. military protection and would likely become subject to the military influence of China. If the yuan spreads wide enough, it could grow as a unit of account, as trade contracts become denominated in it. This structure of incentives implies two expectations:

- Alternatives to the U.S. global monetary system will strengthen.

- Demand for commodity money will strengthen relative to debt-based fiat money.

However, the renminbi is only 2.4% of global reserves and has a long way to go towards international monetary dominance. Countries are much less comfortable utilizing the yuan over the dollar for trade due to its political uncertainty risks, control over the capital account and the risk of dependence on Chinese military security.

A common expectation is that either the West or the East is going to be dominant once the dust settles. What’s more likely is that the system will continue splitting and we’ll have multiple monetary systems emerge around the globe as countries attempt to de-dollarize — referred to as a multipolar system. Multipolarity will be driven by political and economic self-interest among countries and the removal of trust from the system. The point about trust is key. As countries trust fiat money less, they will choose commodity-based money that requires less trust in an institution to measure its risk. Whether or not China becomes the buyer of last resort for Russian commodities, global leaders are realizing the value of commodities as reserve assets. Commodities are real and credit is trust.

Bitcoin is commodity-like money, the scarcest in the world that resides on trustless and disintermediated payment infrastructure. Prior to the invasion of Ukraine, Russia had restricted crypto assets within its economy. Since then, Russia’s position has changed drastically. In 2020, Russia gave crypto assets legal status but banned their use for payments. As recently as January 2022, Russia’s central bank proposed banning the use and mining of crypto assets, citing threats to financial stability and monetary sovereignty. This was in contrast to Russia’s ministry of finance, which had proposed regulating it rather than outright banning it. By February, Russia chose to regulate crypto assets, due to the fear that it would emerge as a black market regardless. By March, a Russian government official announced it would consider accepting bitcoin for energy exports. Russia’s change of heart can be attributed to the desire for commodity money as well as the disintermediated payment infrastructure that Bitcoin can be transferred upon — leading to the third realization.

Realization #3: Crypto asset infrastructure is more efficient than traditional financial infrastructure. Because it is disintermediated, it offers a method of possession and transfer of assets that is simply not possible with intermediated traditional financial infrastructure.

Donations in support of Ukraine via crypto assets (amounting to nearly $100 million as of this writing) demonstrated to the world the rapidness and efficiency of transferring value via just an internet connection, without relying on financial institutions. It further demonstrated the ability to maintain possession of assets without reliance on financial institutions. These are critical features to have as a war refugee. Emerging economies are paying attention as this is particularly valuable to them.

Bitcoin has been used to donate roughly $30 million to Ukraine since the start of the war. Subsequently, a Russian official stated that it will consider accepting bitcoin, which I believe is because they are aware that bitcoin is the only digital asset that can be used in a purely trustless manner. Bitcoin’s role on both sides of the conflict demonstrated that it is apolitical while the freezing of fiat reserves demonstrated that their value is highly political.

Let’s tie this all together. Right now, countries are rethinking the type of money they are using and the payment systems they are transferring it on. They will become more avoidant of fiat money (credit), as it is easily frozen, and they are realizing the disintermediated nature of digital payment infrastructure. Consider these motivations alongside the trend of an increasingly fragmented system of global currencies. We’re witnessing a shift towards commodity money among a more fragmented system of currencies moving across disintermediated payment infrastructure. Emerging economies, particularly those removed from global politics, are postured as the first movers towards this shift.

While I don’t expect that the dollar will lose primacy anytime soon, its creditworthiness and military backing is being called into question. Consequently, the growth and fragmentation of non-dollar reserves and denominations opens the market of foreign exchange to consider alternatives. For their reserves, countries will trust fiat less and commodities more. There is a shift emerging towards trustless money and desire for trustless payment systems.

Alternatives To The Global Monetary System

We are witnessing a decline in global trust with the realization that the age of digital money is upon us. Understand that I am referring to incremental adoption of digital money and not full-scale dominance — incremental adoption will likely be the path of least resistance. I expect countries to increasingly adopt trustless commodity assets on disintermediated payment infrastructure, which is what Bitcoin provides. The primary limiting factor to this adoption of bitcoin will be its stability and liquidity. As bitcoin matures into adolescence, I expect this growth to increase rapidly. Countries that want a digital store of value will prefer bitcoin for its sound monetary properties. The countries most interested and least restrained in adopting digital assets will be among the fragmented developing world as they stand to gain the most for the least amount of political cost.

While these incremental shifts will be occurring in tandem, I expect the first major shift will be towards commodity reserves. Official reserve managers prioritize safety, liquidity and yield when choosing their reserve assets. Gold is valuable in these respects and will play a dominant role. However, bitcoin’s trustless nature will not be overlooked, and countries will consider it as a reserve despite its tradeoffs with gold, to be discussed below.

Let’s walk through what bitcoin adoption could look like:

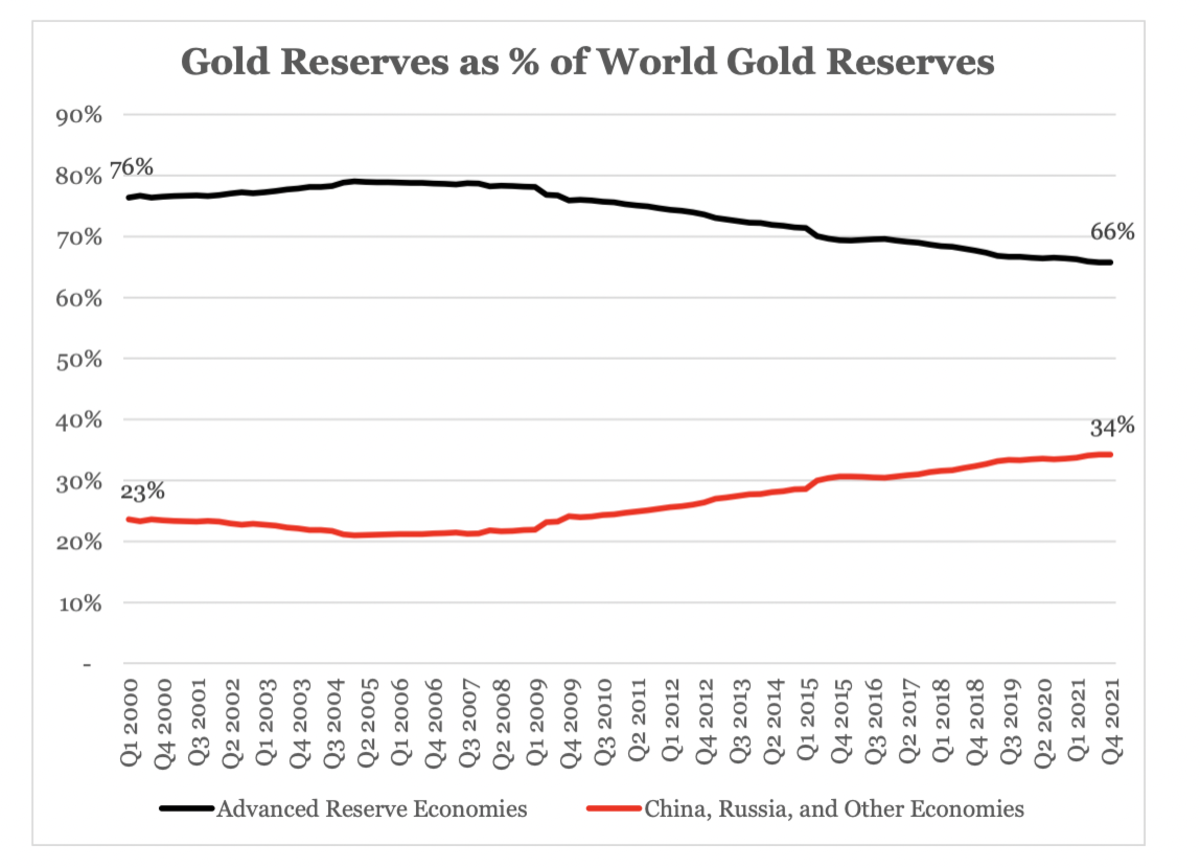

Source: World Gold Council; Advanced reserve economies includes the BIS, BOE, BOJ, ECB (and its national member banks), Federal Reserve, IMF and SNB.

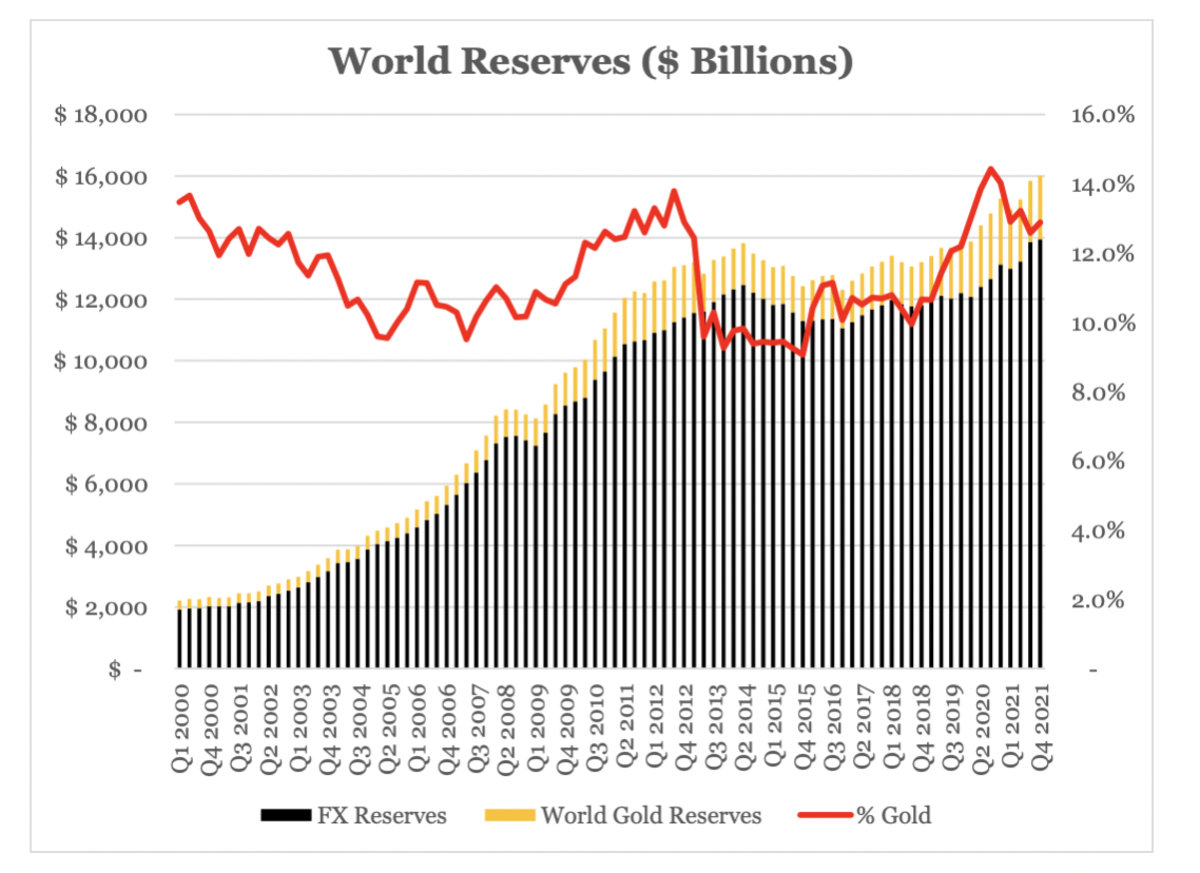

Since 2000, gold as a percentage of total reserves has been declining for advanced economies and growing for China, Russia and the other smaller economies. So, the trend towards commodity reserves is already in place. Over this same period gold reserves have fluctuated between nine and 14% of total reserves. Today, total reserves (both gold and FX reserves) amount to $16 trillion, 13% of which ($2.2 trillion) is gold reserves. We can see in the below chart that gold as a percentage of reserves has been rising since 2015, the same year the U.S. froze Iran’s reserves (this was ~$2 billion, a much smaller amount than the Russia sanctions).

Source: World Gold Council.

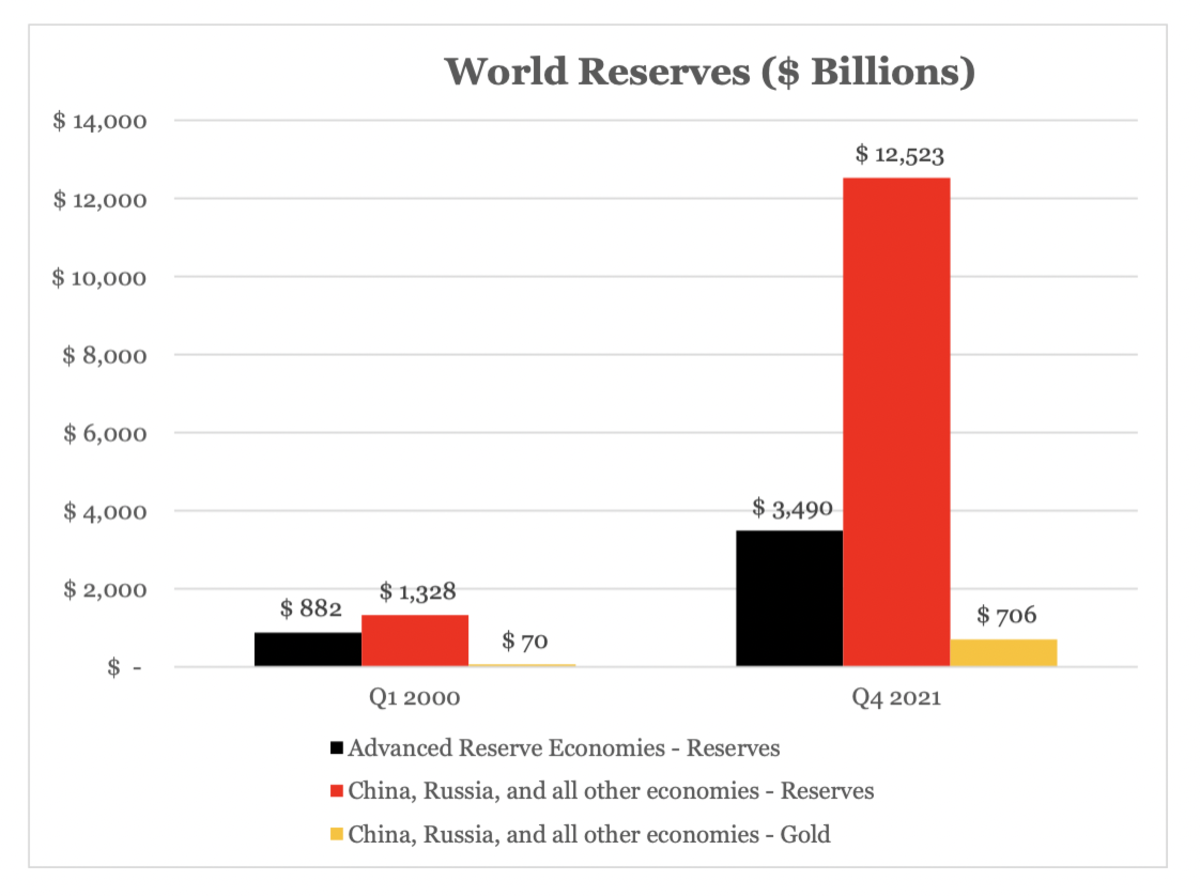

Reserves have been growing rapidly in China, Russia and smaller economies as a whole. The chart below shows that non-advanced economies have increased their total reserves by 9.4x and gold reserves by 10x, while advanced economies have increased total reserves by only 4x. China, Russia and the smaller economies command $12.5 trillion in total reserves and $700 billion of those are in gold.

Source: World Gold Council.

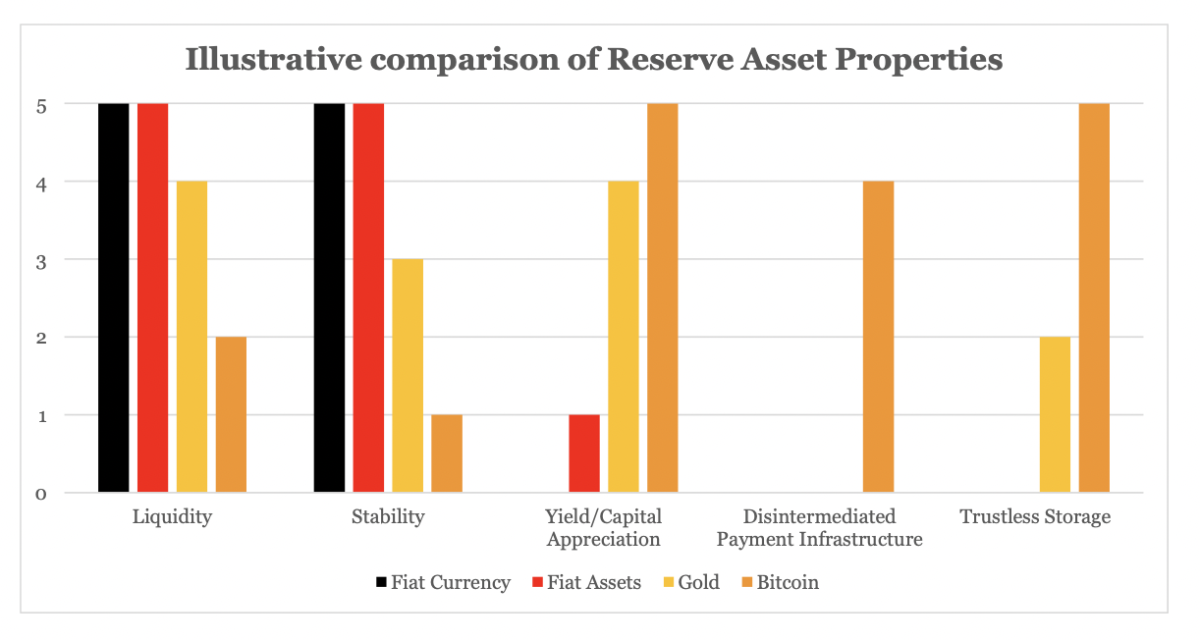

The growth and size of smaller economy reserves is important when considering bitcoin adoption among them as a reserve asset. Smaller countries will ideally want an asset that is liquid, stable, grows in value, disintermediated and trustless. The below illustrative comparison stack ranks broad reserve asset categories by these qualities on a scale of 1-5 (obviously, this is not a science but an illustrative visualization to facilitate discussion):

Countries adopt different reserve assets for different reasons, which is why they diversify their holdings. This assessment focuses on the interests of emerging economies for bitcoin adoption considerations.

Bitcoin is liquid, although not nearly as liquid as fiat assets and gold. Bitcoin isn’t stable. Standard reserve assets, including gold, are much more stable. Bitcoin will likely offer a much higher capital appreciation than fiat assets and gold over the long run. Bitcoin is the most disintermediated as it has a truly trustless network — this is its primary value proposition. Storing bitcoin doesn’t require trusted intermediaries and thus can be stored without the risk of appropriation — a risk for fiat assets. This point is important because gold does not maintain this quality as it is expensive to move, store and verify. Thus, bitcoin’s primary advantage over gold is its disintermediated infrastructure which allows for trustless movement and storage.

With these considerations in mind, I believe the smaller emerging economies that are largely removed from political influence will spearhead the adoption of bitcoin as a reserve asset gradually. The world is growing increasingly multipolar. As the U.S. withdraws its international security and fiat continues to lose creditworthiness, emerging economies will be considering bitcoin adoption. While the reputation of the U.S. is in decline, China’s reputation is far worse. This line of reasoning will make bitcoin attractive. Its primary value-add will be its disintermediated infrastructure which enables trustless payments and storage. As bitcoin continues to mature, its attractiveness will continue to increase.

If you think the sovereign fear of limiting its domestic monetary control is a strong incentive to prevent bitcoin adoption, consider what happened in Russia.

If you think countries won’t adopt bitcoin for fear of losing monetary control, consider what happened in Russia. While Russia’s central bank wanted to ban bitcoin, the finance ministry opted to regulate it. After Russia was sanctioned, it has been considering accepting bitcoin for energy exports. I think Russia’s behavior shows that even totalitarian regimes will allow bitcoin adoption for the sake of international sovereignty. Countries that demand less control over their economies will be even more willing to accept this tradeoff. There are many reasons that countries would want to prevent bitcoin adoption, but on net the positive incentives of its adoption are strong enough to outweigh the negative.

Let’s apply this to the shifts in global reputations and security:

- Reputations: political and economic stability is becoming increasingly riskier for fiat, credit-based assets. Bitcoin is a safe haven from these risks, as it is fundamentally apolitical. Bitcoin’s reputation is one of high stability, due to its immutability, which is insulated from global politics. No matter what happens, Bitcoin will keep producing blocks and its supply schedule remains the same. Bitcoin is a commodity that requires no trust in the credit of an institution.

- Security: because Bitcoin cannot trade military support for its usage, it will likely be hindered as a global medium of exchange for some time. Its lack of price stability further limits this form of adoption. Networks such as the Lightning Network enable transactions in fiat assets, like the dollar, over Bitcoin’s network. Although the Lightning Network is still in its infancy, I anticipate this will draw increased demand to Bitcoin as a settlement network — increasing the store of value function of its native currency. It’s important to understand that fiat assets will be used as a medium of exchange for some time due to their stability and liquidity, but the payment infrastructure of bitcoin can bridge the gap in this adoption. Hopefully, as more countries adopt the Bitcoin standard the need for military security will decline. Until then, a multipolar world of fiat assets will be utilized in exchange for military security, with a preference for disintermediated payment infrastructure.

Conclusion

Trust is diminishing among global reputations as countries implement economic and geopolitical warfare, causing a reduction in globalization and shift towards a multipolar monetary system. U.S. military withdrawal and economic sanctions have illuminated the lack of security within credit-based fiat money, which incentivizes a shift towards commodity money. Moreover, economic sanctions are forcing some countries, and signaling to others, that alternative financial infrastructure to the U.S. dollar system is necessary. These shifts in the global zeitgeist are demonstrating to the world the value of commodity money on a disintermediated settlement network. Bitcoin is postured as the primary reserve asset for adoption in this category. I expect bitcoin to benefit in a material way from this global contraction in trust.

However, there are strong limitations to full-scale adoption of such a system. The dollar isn’t going away anytime soon, and significant growth and infrastructure is required for emerging economies to utilize bitcoin at scale. Adoption will be gradual, and that is a good thing. Growth in fiat assets over Bitcoin settlement infrastructure will benefit bitcoin. Enabling a permissionless money with the strongest monetary properties will spawn an era of personal freedom and wealth creation for individuals, instead of the incumbent institutions. Despite the state of the world, I’m excited for the future.

Whither Bitcoin?

A special thanks to Ryan Deedy for the discussion and review of this essay.

This is a guest post by Eric Yakes. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.