“You can pay for access to a database, buy software or a newsletter by email, play a computer game over the net, receive $5 owed you by a friend, or just order a pizza. The possibilities are truly unlimited.”

This quote is not from a 2011 Bitcoin introduction video. In fact, the quote is not about Bitcoin at all. It is not even from this millennium. The quote is from cryptographer Dr. David Chaum, speaking at the first ever CERN conference in Geneva in 1994. What he’s talking about is eCash.

If the cypherpunk movement has a forefather, the bearded, ponytailed Chaum is it. To say that the cryptographer — now 62 or 63 years old (he won’t reveal his exact age) — was ahead of the curve is an understatement. Before most people had heard of the internet, before most homes had personal computers, before Edward Snowden, Jacob Appelbaum or Pavel Durov were even born, Chaum concerned himself with the future of online privacy.

“You have to let your readers know how important this is,” Chaum once told a Wired journalist. “Cyberspace doesn't have all the physical constraints. […] There are no walls … it's a different, scary, weird place, and with identification it's a panopticon nightmare. Right? Everything you do could be known to anyone else, could be recorded forever. It's antithetical to the basic principle underlying the mechanisms of democracy.”

Chaum, who started his career as a computer science professor at Berkeley University, was not just a digital privacy advocate. He designed the tools to realize it. First published in 1981, Chaum’s paper “Untraceable Electronic Mail, Return Addresses, and Digital Pseudonyms” laid the groundwork for research into encrypted communication over the internet, which would eventually lead to privacy-preserving technologies like Tor.

But privacy of regular communication was not at the top of Chaum’s priority list. He arguably had an even bigger idea. The Berkeley professor wanted to design a privacy-preserving digital money.

“The choice between keeping information in the hands of individuals or of organizations is being made each time any government or business decides to automate another set of transactions,” Chaum would explain in the Scientific American in 1992. “The shape of society in the next century may depend on which approach predominates.”

Ten years prior, by 1982, Chaum had already solved the puzzle, which he had published in his second major paper: “Blind signatures for untraceable payments.” At a point in time when today’s Bitcoin veterans like Dr. Pieter Wuille, Erik Voorhees or Peter Todd had yet to take their first breath, the cryptographer had designed a solution to realize an anonymous payment system for the internet.

Blind Signatures

At the heart of Chaum’s digital money system lies his innovation of “blind signatures.”

To understand blind signatures, it’s important to first remember how public key cryptography works and, in particular, what (regular) cryptographic signatures are.

Public key cryptography uses key pairs. Such a pair consists of a public key, which is a seemingly random string of numbers that is mathematically derived from the other, truly random string of numbers: the private key. With the private key, it’s trivial to generate the public key. But with only the public key, it’s practically impossible to generate the private key: it’s a one way street.

Public key cryptography can be used to establish private communication between two people — in academic circles usually referred to as “Alice” and “Bob” — who only share their public keys with one another. Their private keys remain private.

But private communication is not all Alice and Bob can do. Alice can also cryptographically “sign” any piece of data (and so can Bob). To do so, Alice must mathematically combine her private key with this data. The result will be another seemingly random string of numbers known as the “signature.” Once again, it’s impossible to recreate Alice's private key from the signature (with or without the piece of data). It’s all still a one-way street.

The interesting thing about this signature is that Bob (or anyone else) can check it against Alice’s public key. This tells Bob that it was indeed Alice that created the signature with her private key (and the added piece of data). This can, in turn, mean whatever Alice and Bob want. For example, it can mean that Alice agrees with the content of the data (just like a handwritten signature).

A blind signature then takes all this one step further. This time, Bob first generates a random number, called a “nonce,” and mathematically combines this with the piece of data. This “scrambles” the piece of data to make it seem like yet another random string of numbers. Bob can then give the scrambled data to Alice for her to sign. Alice cannot tell what the original data looks like, so she is “blind signing” it. The result is a “blind signature.”

Now, the interesting thing about this blind signature is that it’s not just linked to Alice’s keys (like any signature would be) and the scrambled data. The same blind signature is also linked to the original, unscrambled data. Using only Alice’s public key, anyone can check that Alice signed a scrambled version of the original data — including, of course, Alice herself, if she does get to see the original data later on.

eCash

This blind signature scheme is the trick that Chaum used to create a digital money system.

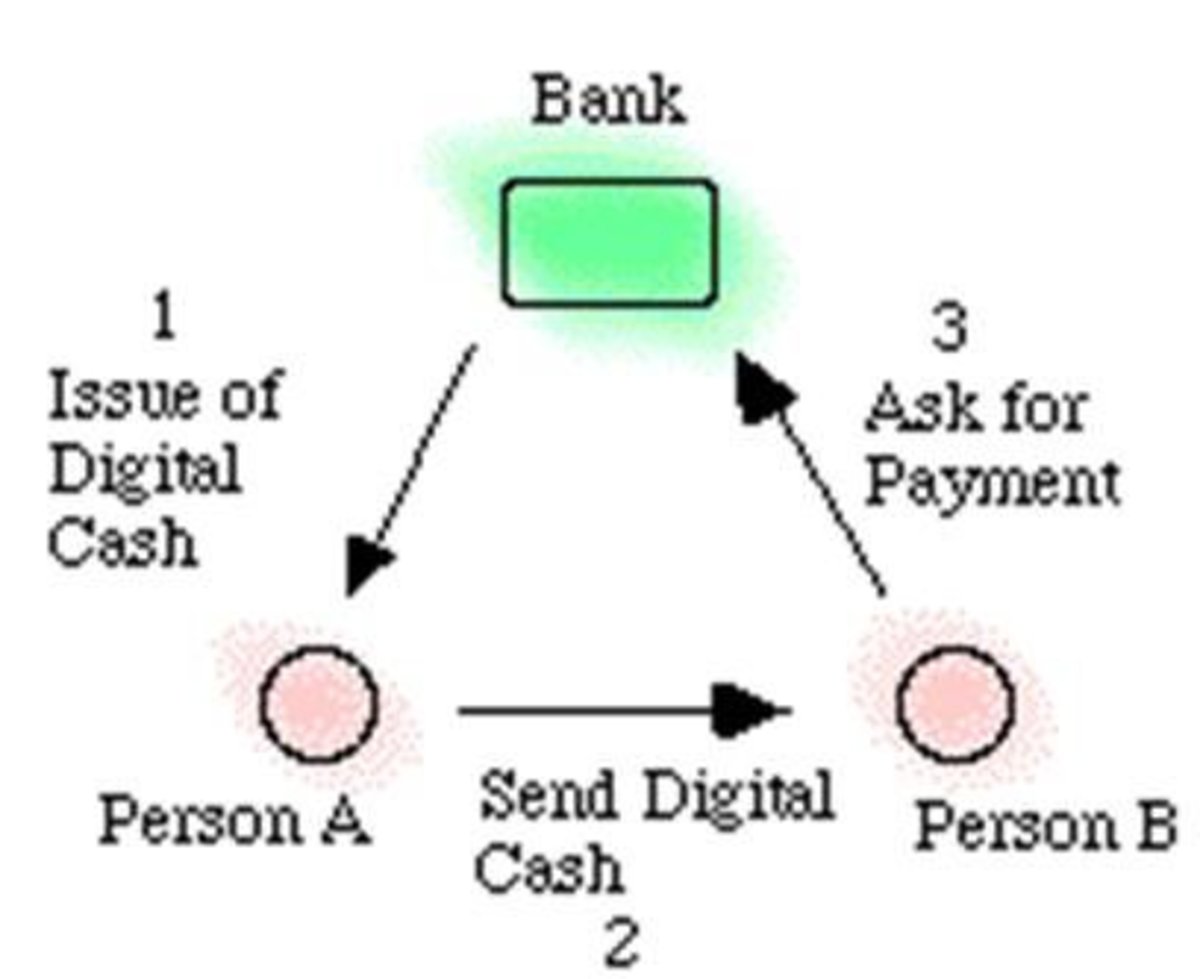

To realize this, Alice from the above example would actually be a bank: Alice Bank. This is a regular bank, like banks exist today, where customers have bank accounts with (in this example) U.S. dollar deposits.

Let’s say Alice Bank has four customers: Bob, Carol, Dan and Erin. And let’s say that Bob wants to buy something from Carol.

First, Bob requests a “withdrawal” from Alice Bank. (Ideally, he had already made this withdrawal earlier — but never mind that for now.) To make this withdrawal, Bob actually creates “digital banknotes” himself, in the form of unique numbers: “serial numbers.” On top of that, he scrambles these banknotes, as shown above. These scrambled banknotes are sent to Alice Bank.

Having received the scrambled banknotes from Bob, Alice Bank then blind signs each scrambled banknote and sends them back to Bob. For each signed, scrambled banknote that she sends back, Alice Bank subtracts one dollar from Bob’s bank account.

Now, because Alice Bank blind signed the scrambled banknotes, her signature is also linked to the original, unscrambled banknotes. So, Bob can now use the original, unscrambled banknotes to pay Carol by simply sending them to her.

As Carol receives the banknotes, she should forward them to Alice Bank. Alice Bank then checks that she indeed blind signed each of the banknotes, which her blind signatures allow her to do: they are linked to her own keys. Alice Bank also checks that the same banknotes (serial numbers) haven’t already been deposited by someone else in order to ensure that they haven’t been double-spent.

As the banknotes check out, Alice Bank adds the equivalent number of dollars to Carol’s bank balance, and lets Carol know. Upon this confirmation, Carol knows she’s been paid valid banknotes by Bob and can safely send him whatever he was buying from her.

The basic idea behind eCash. Source: faculty.bus.olemiss.edu/

Of key importance, Alice Bank will see the unscrambled banknotes for the first time only when Carol deposits them! As such, Alice Bank has no way of knowing that the banknotes were Bob’s. They could just as well have come from Dan or Erin.

As such, Chaum’s solution offers privacy in payments. This was not new in itself, of course: private payments were the norm in those days. But it was new in digital form. Hence, Chaum’s analogy: cash. Electronic cash. eCash.

DigiCash

By 1990, a little under 10 years after finishing his first papers (younger cryptocurrency developers like Matt Corallo, Vitalik Buterin and Olaoluwa Osuntokun still hadn’t been born), David Chaum founded DigiCash. The company was based in Amsterdam, where Chaum had been living for a couple of years, and specialized in — indeed — digital money and payment systems. These included a government project to replace toll booths (which was eventually cancelled) and smart cards (akin to what we call hardware wallets today). But DigiCash’s flagship project was its digital cash system, eCash. (The system was called eCash, while the money in the system was dubbed “CyberBucks,” comparable to using capital-letter Bitcoin for the protocol and lower case bitcoin for the currency.)

The technical team in the early days of DigiCash. (Chaum not pictured.) Source: chaum.com/ecash

At a time that Netscape and Yahoo! were leading the tech industry to new heights, and where some thought micropayments, not advertisements, would be the revenue model for the web, DigiCash was considered a rising star by tech entrepreneurs of the day. Of course, Chaum and his team had much faith in their technology as well.

“As payments on the network mature, you’re going to be paying for all kinds of small things, more payments than one makes today,” Chaum told the New York Times in 1994, of course, emphasizing the importance of privacy in such a world. “Every article you read, every question you have, you’re going to have to pay for it.”

That year, after four years of development, the first successful payments were tested, and later that same year eCash trials began: Banks could acquire a license from DigiCash to use the technology.

Interest was significant. By late 1995, eCash was licensed to its first bank: the Mark Twain Bank in St. Louis. Moreover, by early 1996, one of the biggest banks in the entire world got on board: Deutsche Bank. Credit Suisse, a second major player joined later, and several other banks across different countries — including the Australian Advance Bank, Norway’s Norske Bank and Bank Austria — would follow suit.

Yet, what’s perhaps more interesting than the deals DigiCash struck are the deals it did not. Two of the three major Dutch banks — ING and ABN Amro — are said to have made DigiCash partnership deals worth tens of millions of dollars. Similarly, Visa reportedly offered a $40 million investment, while Netscape had interest as well: eCash could have been included in the most popular web browser of that era.

Still, the biggest offer of all probably came from none other than Microsoft. Bill Gates wanted to integrate eCash into Windows 95 and is said to have offered DigiCash some $100 million to do so. Chaum, so the story goes, asked for two dollars for each version of Windows 95 sold. The deal was off.

While a rising star in the minds of technologists of the day, DigiCash seemed to have trouble making a financial deal that would help it to realize its full potential.

By 1996, DigiCash employees had seen one failed deal too many and wanted a change in policy. This change came in the form of a new CEO: Visa veteran Michael Nash. The startup also got a fund injection, while MIT Media Lab founder Nicholas Negroponte was made chairman of the board. (Through its Digital Currency Initiative, the MIT Media Lab employs several Bitcoin Core contributors today.) The DigiCash headquarters were moved from Amsterdam to Silicon Valley. Chaum remained part of DigiCash, but now as CTO.

It wouldn’t make much difference. After several years of trials, eCash wasn’t catching on with the general public. The banks that got on board were experimenting but did not really push the technology; by 1998, Mark Twain Bank had only enrolled 300 merchants and 5,000 users. While a final deal with Citibank came close — it could have given the project a good push — this bank ended up walking out for unrelated reasons.

“It was hard to get enough merchants to accept it, so that you could get enough consumers to use it, or vice versa,” Chaum told Forbes in 1999, after DigiCash had finally filed for bankruptcy. “As the Web grew, the average level of sophistication of users dropped. It was hard to explain the importance of privacy to them.”

The Spawning of a Cypherpunk Dream

DigiCash failed, and eCash failed with it. But even though the technology did not succeed as a business, Chaum’s work would inspire a group of cryptographers, hackers and activists, connected through a mailing list. It was this group — which included DigiCash contributors like Nick Szabo and Zooko Wilcox-O’Hearn — that would come to be known as the cypherpunks.

Perhaps a bit more radical than Chaum himself ever was, the cypherpunks kept the dream of an electronic cash alive, proposing alternative digital currency systems throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. In 2008, about 10 years after DigiCash’s demise, Satoshi Nakamoto sent his proposal for an electronic cash to the de-facto successor of the then-defunct cypherpunk mailing list: Bitcoin.

Bitcoin and eCash have little in common from a design perspective. Crucially, eCash was centralized around DigiCash and could not really be its own currency. Even if every single person in the world would only use eCash for all their transactions, banks would still be necessary to offer account balances and confirm transactions. This also means that eCash — while providing privacy — was not as censorship resistant. Where Bitcoin was able to keep WikiLeaks funded even through a banking blockade, for example, eCash could not have done the same thing; banks could still have blocked WikiLeaks’ accounts.

Still, Chaum’s work on digital currency, dating back to the early 1980s, remains relevant. While Bitcoin itself does not employ blind signatures, scaling and privacy layers on top of the Bitcoin protocol could. Bitcointalk forum and r/bitcoin subreddit moderator Theymos, for example, has been a champion of an eCash-like scaling sidechain for Bitcoin for some time. Adam Fiscor, a leader in the domain of Bitcoin transaction privacy today, is realizing coin-mixing services utilizing blind signatures, as once proposed by Bitcoin Core contributor Greg Maxwell. And yet-to-be-announced Lightning Network technology could utilize blind signatures to improve security.

And Chaum himself? He returned to Berkeley, where he is responsible for a long list of publications, many in the field of digital elections and reputation systems. Perhaps, some 20 years from now, an entirely new generation of developers, entrepreneurs and activists will look back at these as the groundwork for a technology that is about to change the world.

This article is partly based on two articles published in the 1990s: “E-Money (That’s What I Want)” by Steven Levy for Wired, and “Hoe DigiCash alles verknalde” (Translated: “How DigiCash Blew Everything”) by an unknown author for Next! Magazine. There is also a wealth of information on chaum.com/ecash.