Stephen Thompson is a senior technical editor at LQwD Fintech Corp. He was a Bitcoin researcher and investigator at BIGG Digital Assets, carrying out Bitcoin investigations with analysis of on-chain and off-chain information.

Trust is the lifeblood of all social interactions. In an environment with high levels of trust, people can make transactions in full confidence that their counterparties are who they say they are, and will behave to both party’s satisfaction. If there is low trust in a society, the social consequences are manifold, unpredictable and often violent. People build structures and institutions that act as proxies for trust, but those structures can go wrong in ways that can become detrimental to everyday social life. For example, a bank’s network fails, leaving a transaction incomplete; a government that starts doing the opposite of what it says it will do; a website claiming to uphold free speech that starts censoring undesirable comments.

How The Internet Changed Trust

In our increasingly technologized world, society has come to see the use of electronic proxies for communication, commerce or even as a way of passing the time, as entirely normal. We have built networks that enable people to enter trusted relationships without ever having met each other. The most expansive network we have built is the internet. The internet’s most familiar app, the World Wide Web, started off as a platform that held vast amounts of information. However, there was so little going on with these early web pages that a 56k modem on a phone line was sufficient to call them up. The internet started to become more powerful and much more interactive in the mid-2000s with the arrival of e-commerce, social media and networking. It became possible for people to use the internet to transfer money and their personal information. This upgrade in the internet’s capability required a new kind of trust: trust that people’s money and personal information was safe in the hands, not of another person, but of a machine, and not just of one machine, but getting transferred between machines and sometimes across different networks.

A study by the Pew Research Center in 2017, surveyed people’s attitude to the kind of trust people had for holding money and personal information on a digital platform. The respondents answered a range of questions but here are some of the types of answers they gave:

- A combination of better technology with people allowing it to play a more prominent role in their lives will improve trust.

- Government and industry regulation tailored to the nature of the internet will improve trust.

- Trust itself will be fluid depending on the context.

- Compliance replaces trust as part of a “new normal” if users still want the fruits of the internet’s functions.

- Blockchain can improve elements of the internet but it will not be so disruptive by the time it becomes universally adopted.

- Governments and corporations have no interest in improving trust over the internet and criminal networks will undermine trust.

I have focused on money and personal information because, in the digital world, those two attributes have merged into what has become known as “digital assets.” Information has just as much value as money. Meanwhile, nefarious actors have organized themselves into networks which have become adept at attacking other networks. Such nefarious networks are just as likely to be seeking personally-identifiable information as they would be seeking money. The WannaCry virus of 2017 was one such example where the hackers were seeking digital information as well as funds.

Bitcoin As A New Trust Layer For The Internet

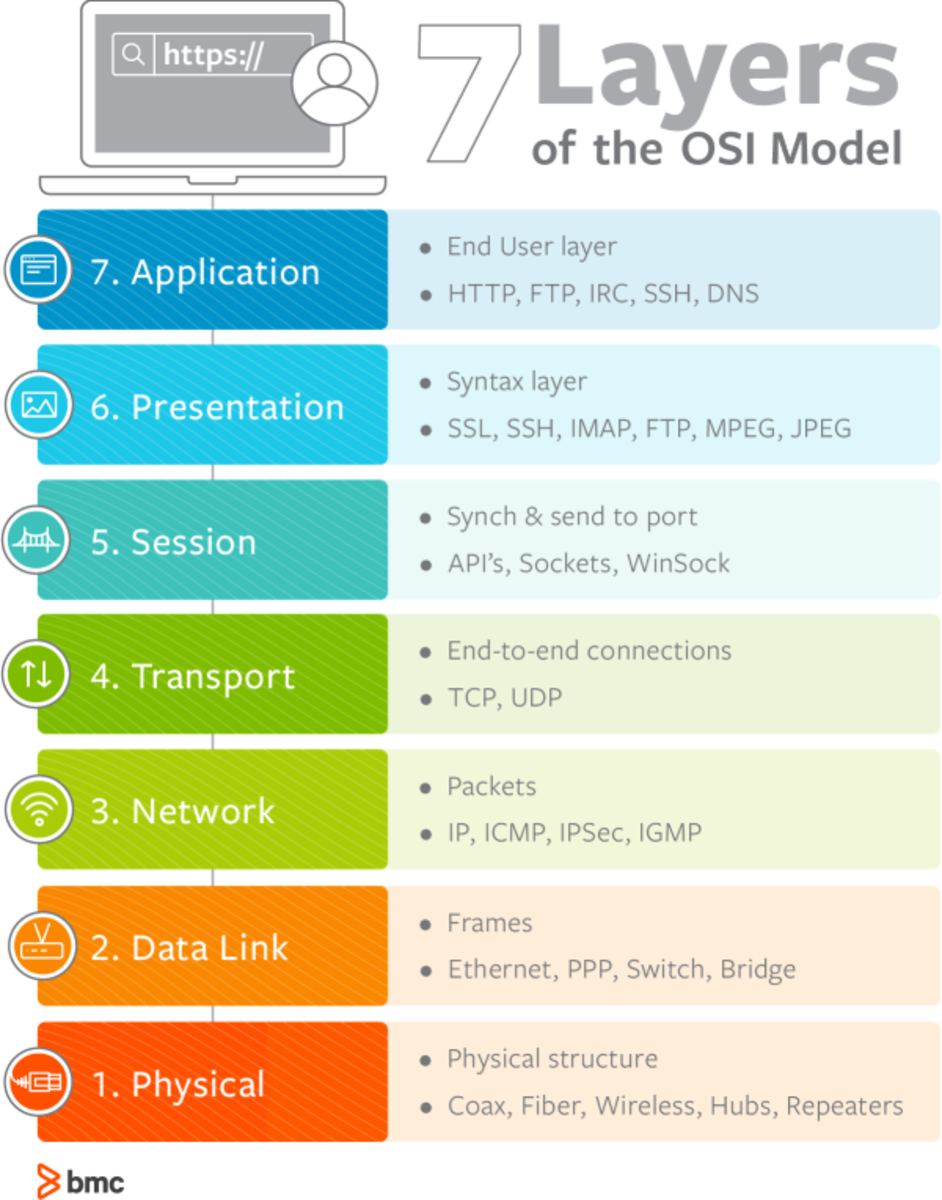

The internet currently has seven layers as expressed in this model below. This is the Open Systems Interconnections model (OSI).

(Source)

The model describes seven layers (from bottom to top):

- Physical layer for the transfer of raw data.

- Data link layer which secures links between networked computers or nodes.

- Network layer that controls the secure transfer of data packets from a node on one network to a node on another network (like what a VPN would do).

- Transport layer which transfers data sequences of differing lengths from one application to another.

- Session layer controls the setup of connections between computers which run logins, name lookup and logouts.

- Presentation layer arranges the data into a format that the application layer can view.

- Application layer is where the user manipulates software, such as Microsoft Office or web browsers, so that it communicates between the client and server to perform certain tasks.

It has been argued that this OSI model needs a trust layer that does not create a single point of failure — like downtime — at any stage of the user’s interaction with the internet.

This is where Bitcoin comes in. You can speak of Bitcoin the network or bitcoin the asset, but in both cases, one can argue that Bitcoin combines money and information. The Bitcoin network is a trust protocol and we see it as the essential trust layer for the internet. The Bitcoin protocol is a set of rules that govern the network and protect it from attacks, like tampering with the blockchain, double-spending or spamming the network. We consider Bitcoin as a much-needed trust layer for the internet because it is trustless. How can this be? “Trustless” means that there are no entities that users have to trust in order to get their information from one node to another and its eventual confirmation onto the network. Instead, the decentralized nature and transparency of the network is the base on which Bitcoin’s trust protocol sits. Bitcoin’s own trust protocol runs on two levels: the transaction level, where users in a transaction swap their public keys and then sign transactions with their private keys so that both users can know that the transaction was genuine; the network level where thousands of nodes and miners confirm that the transaction was not spent twice and then broadcast to the blockchain.

Proof-Of-Work For Analytics

What would be the mechanism that can make Bitcoin a viable trust layer for the internet? In our book “Trust and the Rise of Bitcoin,” we have proposed “proof-of-work for analytics,” which refers to the amount of computational effort required to audit the Bitcoin ecosystem in real time. Users, individually or in a pool, can apply this proofing by running a full node that surveils internet data about the current state of the blockchain. At the moment, there are thousands of full nodes doing just that. Proof-of-work for analytics helps to deter world governments and their corporate agencies from mass surveillance as well as abusive data mining. The greater the number of full nodes analyzing the blockchain, the more data points there will be. Proof-of-work for analytics can be applied to those areas of the internet where users’ private information is most vulnerable to mass surveillance, such as on social media. Basically, we are proposing that the Bitcoin protocol, using the proof-of-work algorithm, can provide the internet with a much-needed layer of trust.

External Factors That Impact On Trust

There are other factors that will influence the prospects of the Bitcoin protocol in improving trust in the internet. The blockchain industry, financial regulators and law enforcement agencies will have an impact on Bitcoin as a trust layer for the internet. Will their interventions assist or hinder blockchain technology in being trustworthy from the public’s point of view?

This is where we move away slightly from the Bitcoin-centric notion of trust and toward the type of trust where new users are willing to use Bitcoin not only because they trust the network to carry out the functions that the protocol promises, but also because they have assessed their trust of Bitcoin based on what they have heard from the words and actions of blockchain companies, regulators and law enforcement agencies. We need to deal with this layman’s idea of trust because the computational trust of the Bitcoin protocol becomes a non-starter if users do not have conventional trust in Bitcoin.

When we look at the blockchain industry, centralized exchanges have been the shop window for bitcoin. If something goes wrong with an exchange anywhere, be it a denial-of-service attack, funds stolen or the like, the public tends to think that the Bitcoin blockchain itself has been hacked. The mainstream news loves personalities, so, individuals such as Gerald Cotten of QuadrigaCX, Alexander Vinnik of BTC-e and Ross Ulbricht of the Silk Road dark web marketplace, have all played their part in making bitcoin look like a currency that only renegades would use. The voice of the Bitcoin community is barely heard for two reasons: The community’s information is not the public’s go-to source and the emotive explanations that come from the mainstream news media overpower the technical explanations of the Bitcoiners. Instead, it is the mainstream news media who, as we all know, have a taste for remarking, “Bitcoin is going down to zero,” or “Bitcoin is too volatile,” or “Bitcoin is used by criminals,” or most recently, “Bitcoin uses too much energy.” With that level of discourse, where is the opening into which we can introduce the concept of computational trust? Or even that the energy consumption involved in Bitcoin mining — which is low compared to other industrial practices — is the price one pays for the decentralization and transparency that Bitcoin offers?

The public sees the evolving relationship between Bitcoin and regulators. Bitcoin has come under the scrutiny of financial regulators albeit at different times, depending on the region. For instance, the Mt. Gox collapse in 2014 awakened the East Asian regulators to Bitcoin, but it took the revelations from the Panama Papers in 2016, to bring cryptocurrencies to the attention of European regulators. Financial regulators around the world believe that bitcoin needs to come under financial regulation before it can ever hope to win people’s trust and then attain the mass adoption that Bitcoiners have so often promised themselves.

The financial regulators have, for the most part, aimed at the centralized exchanges as they are the largest businesses that stand at the bridge between fiat currency and cryptocurrencies. But regulators faced a fundamental problem: Bitcoin is a global network which runs the same protocol wherever in the world the user might be. Regulators are nation-state-level organizations whose existence predates Web 2.0 and, for some, the internet itself: The UK’s Financial Conduct Authority was established as the Financial Services Authority in 1997, the United States’ Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) — that has been recently assigned the regulation of bitcoin — was set up in 1974. Those two organizations were set up to regulate specific forms of financial activity. The success of their efforts to cover bitcoin with their regulations (beyond centralized exchanges), remains to be seen.

Meanwhile, Bitcoin keeps evolving away from these attempts. An even bigger challenge is it has so far proven difficult for regulators to coordinate their policies to emulate Bitcoin’s global protocols. In 2018, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) offered regulators some hope when it published global guidelines that governments could apply to their own legislation and give their regulators a better degree of synergy when dealing with cryptocurrencies.

The FATF published its first set of recommendations applying to bitcoin in 2018. It required businesses that transferred any form of digital currency to be termed as VASPs (virtual asset service providers). Centralized exchanges were among those businesses facing these new requirements. Most significantly for bitcoin, the FATF was looking to apply the “travel rule” to bitcoin transactions. Those VASPs receiving bitcoin worth $10,000 or more were required to report the transaction amount, the payer’s real information and account number to their local law enforcement agencies and financial intelligence units as though the transaction was an act of money laundering or terrorism financing. This points to the FATF’s belief that labeling bitcoin transactions with real information will improve trust in bitcoin.

The nature of their attempts at cryptocurrency regulation have focused on money laundering and terrorist financing, so a key focus of regulation has been to require the exchanges to complete know-your-customer (KYC) and anti-money-laundering (AML) checks on new users.

Conclusion

Bitcoin is an open-source monetary network that conceives of trust as computational effort in the form of proof-of-work. The effort by regulators to achieve trust involves breaking of Bitcoin’s trust protocols that make it secure — pseudonymity being one of them. In effect, regulators’ trust requires the breakup of Bitcoin’s trust. The blockchain industry really is caught in the middle as they try to persuade the public to adopt this new kind of money while under pressure to comply with regulators’ conception of trust, during which, they may be called upon to run public-relations damage-limitation exercises whenever their platforms are attacked. We look forward to the success of Bitcoin, as it provides an avenue of computational trust that vouchsafes the security of the network — something that central bank-controlled fiat currencies are not designed to do.

This is a guest post by Stephen Thompson. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc. or Bitcoin Magazine.