A recently published economic research paper argues that a global cryptocurrency would make international monetary policy impossible.

Can cryptocurrencies like bitcoin wreck central banking? “The short answer is yes,” wrote Pierpaolo Benigno, a professor of economics at Rome’s Libera Università Internazionale degli Studi Sociali (LUISS), in an article published on April 26, 2019.

On August 19, 2019, Benigno and two other economists, Linda M. Schilling and Harald Uhlig, published a paper expanding on this short answer, “Cryptocurrencies, Currency Competition and the Impossible Trinity,” attempting to mathematically prove it to be true.

Citing a range of economic thought — from the authors’ previous work; to Fredrick Hayek, the renowned thinker of the Austiran School of Economics; and Nobel prize winning crypto skeptic Paul Krugman — the paper applies Bitcoin research to economic standards of international monetary policy with the end goal of examining how monies issued outside of governments (including truly decentralized cryptocurrency like bitcoin and centrally-issued digital currencies like Facebook’s libra) would impact traditional currencies.

Through a series of string theory-like calculations, the paper highlights a general question that Bitcoiners, media wonks and economists have speculated on for years: What does the introduction of cryptocurrency mean for the world’s central bank economies? This paper’s approach is in line with a similar paper recently covered by Bitcoin Magazine, with more of a predictive lens of what characteristics a truly “global (crypto)currency” would require.

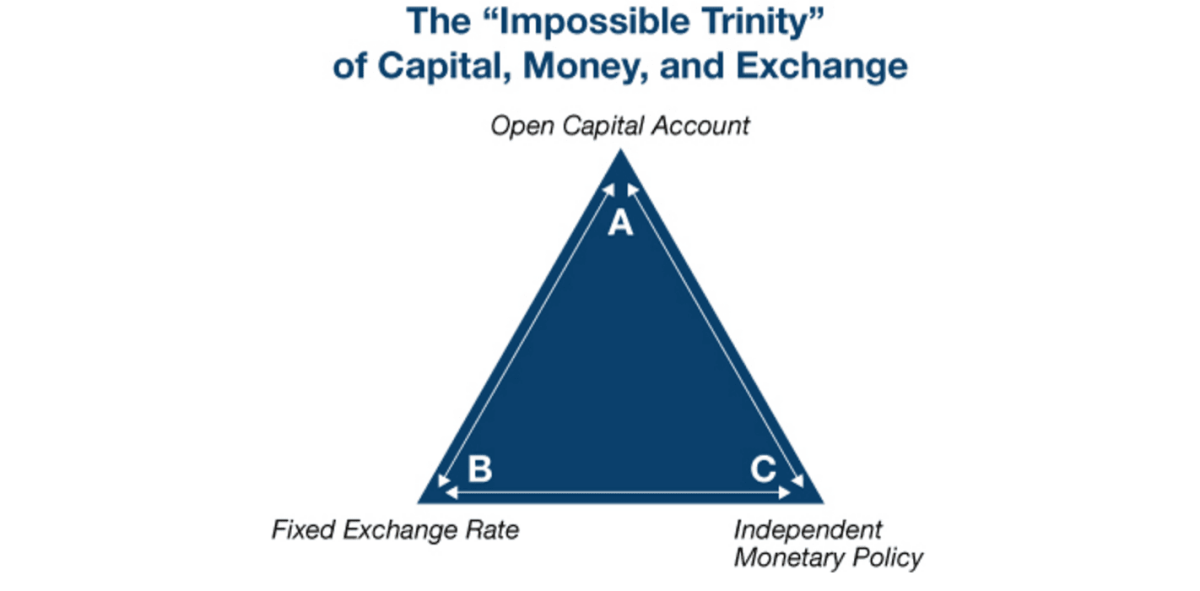

In essence, the researchers argue that the presence of global cryptocurrencies make the “impossible trinity” — an international economic concept that argues it is impossible to maintain a 1) fixed foreign exchange rate, 2) free capital movement free of capital controls and 3) an independent monetary policy — even less possible.

Motivation and Method

Although the authors argue that global currencies are not a new phenomenon (for example, “Spanish Dollar in the 17th and 18th century, gold during the gold standard period, and the U.S. Dollar since then”), cryptocurrencies are a new phenomenon because they seek to become a means of payment. At even levels of liquidity — i.e., usability and acceptance — this will put them in direct competition with national currencies for transactional purposes.

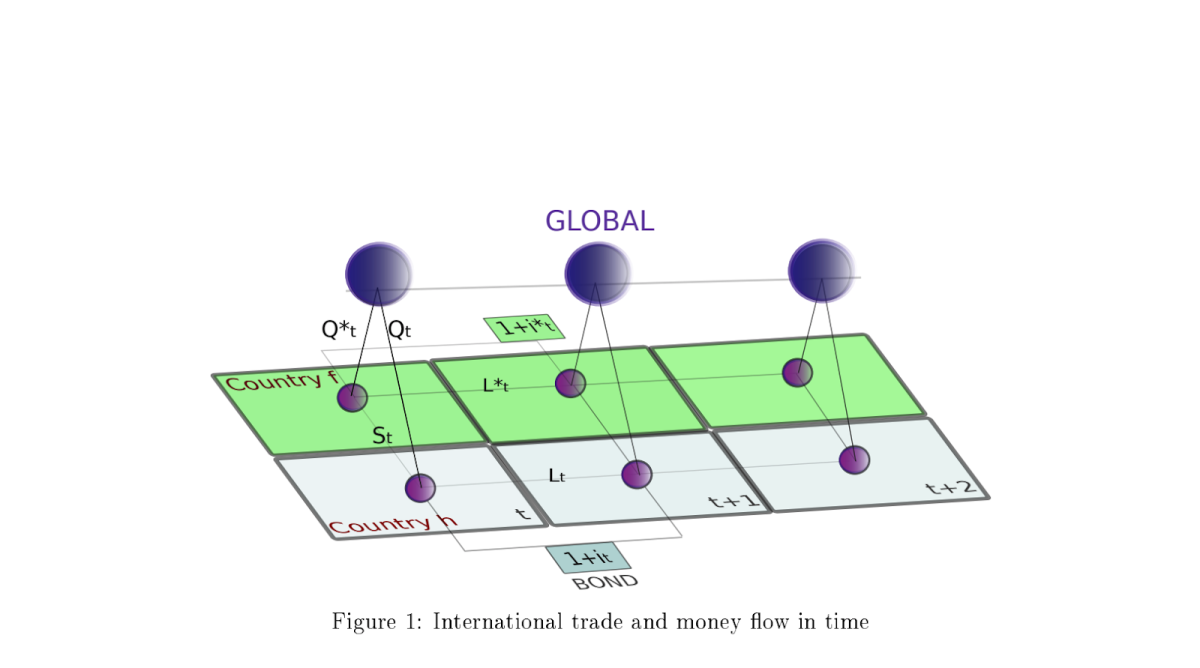

Under these assumptions, the research analyzes a “two-country economy featuring a home, a foreign and a global (crypto)currency.” The paper also assumes that the aforementioned global cryptocurrency is used in both countries, that the markets for each currency is complete and each currency’s “liquidity services are rendered immediately.”

Based on standard approaches to economic policy, the model shows that, eventually, the global cryptocurrency would equalize interest rates and the exchange rate between the home and the foreign currency would become “a risk-adjusted martingale,” meaning predictable.

Because it is used in both countries, this economic phenomenon would come from the global cryptocurrency creating a kind of tether between all domestic and foreign currencies, what the authors’ call a “Crypto-Enforced Monetary Policy Synchronization (CEMPS).”

According to the paper, once this synchronization occurs, central banks would have an extremely difficult time regaining an independent monetary policy — this is where, the researchers argue, the impossible trinity becomes more impossible.

The impossible trinity argues that, if you’re managing a central bank, you have three options:

- Setting a fixed currency exchange rate (for instance, the pound and dollar were pegged several times throughout the 20th century; and in 2018, Iran reportedly set a fixed exchange rate of 42,000 rials to the USD.

- Allowing capital to flow freely without an exchange rate.

- Creating an independent monetary policy.

The trick behind the impossible trinity is that only one side of the triangle can be achieved at any given time. Once a global cryptocurrency comes into play, bitcoin or something else, each individual country’s currency must compete with the global cryptocurrency within its own financial market. As the paper states, “this shows that nominal interest rates must be equal and the exchange rate would have to be risk-adjusted.”

The only way for a central bank to make its domestic currency more attractive than the global cryptocurrency, what the paper calls the “escape hatch,” ends in a race to the bottom. Theoretically, one country lowers the interest rate of its own currency in order to lower the opportunity cost for holding that currency and make it more attractive than the global cryptocurrency as a means of payment.

“This escape hatch is not particularly attractive, however,” states the authors. “Nominal interest rates can only be lowered to zero. Furthermore, a rat race between the two central banks may then eventually force both to stick at the zero lower bound forever or at quite low interest rates.”

This outcome would risk deflationary spirals, macroeconomic damages or a potential abandonment of the domestic currency in favor of the global cryptocurrency. The concern being that these perceived dangers would further limit a central bank’s ability to maneuver in order to stabilize its economy.

Bitcoin and Gresham's Law

For this scenario to play out, the global cryptocurrency would need to provide liquidity services that could be rendered immediately. If we decide that bitcoin is this global cryptocurrency, then it would have to become a satisfactory alternative method of payment that can compete with each country’s domestic currency. Though it has the greatest market capitalization of any cryptocurrency, bitcoin’s level of scale and adoption by users and merchants is nowhere close to where it needs to be.

However, bitcoin does share similarities to possibly the closest thing to a global currency that exists today: gold. Gold is not considered legal tender in the U.S., yet people have hoarded it for centuries. The effect of investors holding onto one asset while using another as a medium of exchange is known as Gersham’s Law. In short, Gersham’s Law states that bad money drives better money out of circulation. But Gresham's Law only applies when two forms of money in circulation are accepted by law as having similar face value. Despite the fact that Gersham’s Law doesn’t apply to bitcoin because its value isn’t dictated by any state, the paper argues that something akin to it would play out within a country where both a global cryptocurrency and domestic currency are used. Here, it might be assumed that the state would impose some law. On the macro level, this law confirms the research paper’s conclusion that, where the global cryptocurrency would represent “good” money, a domestic currency would become the “bad” money. Added to that, Gersham’s Law would also certainly reinforce and increase hodling as the same kind of hoarding behavior for good money, but in that scenario, with bitcoin.

While most economists would argue that it’s far too early to truly compare bitcoin and gold, in its first decade of existence, the cryptocurrency has performed far better than gold. The paper accounts for this by assuming that the global cryptocurrency would require much higher levels of liquidity than gold. And bitcoin does offer much higher levels of liquidity for cross-border transactions.

Not Orange Coin?

Of course, other cryptocurrencies could become the “global cryptocurrency” defined in this paper.

However, a government-backed cryptocurrency would not really work within this model because 1) the authors of the paper assume this global cryptocurrency would be accepted throughout the world and this would seem impossible unless the political world changed drastically; and 2) a government-backed cryptocurrency would not demonstrate the same store-of-value properties as gold and bitcoin, meaning that government-backed cryptocurrencies would presumably have much lower levels of liquidity in cross-border transactions than bitcoin, particularly when dealing with other central banks.

The only other cryptocurrencies that could fit the requirements would have to be privately issued. Although bitcoin’s market capitalization dwarfs all other cryptocurrencies in existence, Facebook’s libra is named as part of the motivation for the paper. Because Facebook is not a nation, libra is no less of a private money than bitcoin is, in this context.

“10 years after the introduction of Bitcoin, Facebook is seeking to launch Libra designed to appeal to its more than 2 billion world-wide members,” according to the paper. “Other companies are not far behind. While other means of payments have been in worldwide use before, the ease of use and the scope of these new cryptocurrencies are about to create global currencies of an altogether different quality.”

Furthermore, libra’s backing as a basket of other cryptocurrencies indicates that it might present more pressure than bitcoin does on government-backed currencies because it can compete as in its asset-backed design.

The paper accounts for this by indicating that the same currency competition would intensify if the global cryptocurrency is asset-backed. This would mean that the global cryptocurrency could create bonds within its liquidity services, “thus combining both the advantages of the liquidity services of money with the interest payments of bonds.”

It has been stated that libra will have both of these features. Although bitcoin is not backed by any other assets, the “world’s first genuine Bitcoin Bond” has already been launched.

If there is to be a global cryptocurrency that truly disrupts the world’s central bank economies, perhaps the largest question left unanswered in the paper is whether or not the global cryptocurrency would be backed by assets. Either way, the paper is certain that international policy will be changed and central banks will lose control.