After the embarrassing failure of the DAO in 2016, the Ethereum Foundation moved quickly to address the problem by implementing a hard fork. On July 20, 2016, the new code went into effect, reversing transactions that allowed a hacker to bleed $50 million out of the $150 million venture fund in the wee hours of June 17.

That DAO hard fork was not popular, but it was effective. The majority of miners moved over to the new chain, and the DAO funds went into a new smart contract, so the original investors could safely withdraw their funds.

To be clear, the Ethereum network itself was not hacked, just the DAO smart contract. The hacker took advantage of a loophole in the contract code, written in the JavaScript-like language Solidity.

But while the hard fork was an expedient solution to a pressing problem, how the decision-making was handled has long-term consequences for Ethereum.

Loss of Trust

When the hacker drained the account, she/he put the funds in a child DAO. To extend the mandatory hold on those funds before the hacker could cash out, on June 24, the Ethereum Foundation incented miners to soft fork by releasing Geth version 1.4.8, code-named “DAO Wars.” However, the soft fork was abandoned because of the risk of a denial-of-service attack.

The Foundation then began work on a hard fork to reverse the DOA transactions. Unlike a soft fork, a hard fork is a radical change in the protocol that all stakeholders in a blockchain need to agree upon to implement.

Not everyone agreed with reversing the DAO funds. Many vehemently opposed it. Yet, as events unfolded, it became clear that Ethereum had no structure in place for settling these differences — no official forum for discussing the events, and no official voting mechanism. Instead, decisions were being made on the fly.

As a result, the broader Ethereum community was awakening to the reality that the Ethereum Foundation and its core developers were the ones holding the cards. And there were clear conflicts of interest: the DAO was founded by former Ethereum developers, and several people in the Ethereum Foundation owned DAO tokens.

Stakeholders Not Fully Involved

To get the vote needed to push through a hard fork, on July 15, the Ethereum Foundation turned to Carbonvote, an ad hoc polling tool created after the DAO hack. Ether holders were given one vote per ether they held.

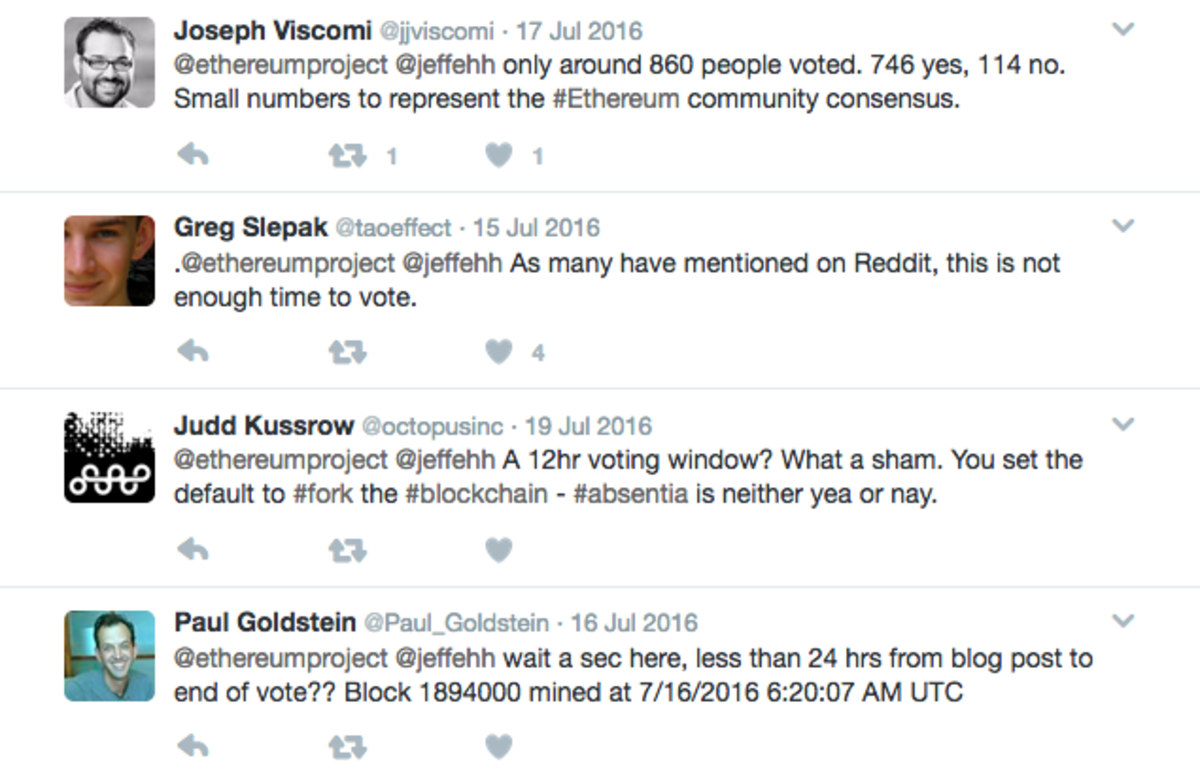

But many questions arose regarding how the vote was handled: whether voters had enough time to vote (the voting window closed in less than 24 hours), who knew about the vote (outside of a blog post, it was only publicized on Twitter and Reddit) and whether enough people even participated to make it legitimate. Only a small percentage of ether holders ever voted. Additionally, questions arose about whether Carbonvote was even an appropriate voting tool. (Ethereum founder Vitalik Buterin had previously referred to it as an informal signaling tool to see “which way the wind is blowing.”)

(Screenshots of https://twitter.com/ethereumproject/status/753877284155777024)

The Ethereum Foundation and core developers ignored the interests of the stakeholders to push forward their own agenda for the fork.

There’s no suggestion that the Ethereum Foundation acted out of anything other than good faith. The problem is the system depends on that good faith — and the broader Ethereum community now knows it.

A Fractured Network

When a hard fork goes through, the hope is that everyone switches over to the new protocol and that the old, deprecated chain simply dies off. But in the case of the post-DAO hard fork, that didn’t happen. Several miners, developers and stakeholders remained on the old blockchain, now called Ethereum Classic.

Now we have two Ethereums. This has divided the once-unified Ethereum community and may dilute its overall influence.

Additionally, forks create security problems. The fewer nodes a network has (when validators leave the system), the less secure it is from takeover attempts. Forks can also create opportunities for replay attacks, where a valid transaction on one fork can be repeated on the other, wreaking havoc in the system.

For maximal security, and the sake of the community, hard forks need to happen in a way that reduces friction and convinces everyone to join the new fork. The fact that this didn’t happen with Ethereum shows that the process lacks consensus.

Hard Forks Are Not Effective for Evolutionary Change

A few months after the DAO fork, both Ethereum and Ethereum Classic came under a sustained denial-of-service attack. Both currencies followed up with subsequent forks to fix the security problems. Additionally, Ethereum planned three upgrade forks: Homestead (which launched in March 2016), Metropolis and Serenity.

Soft forks and hard forks are becoming an accepted way of life for blockchains, and that is dangerous. Any fork has the potential to become controversial, and those controversies can weaken a network and stall future growth, just as with the post-DAO fork in Ethereum and the seemingly endless Bitcoin block size debate.

The process of evolving the Ethereum protocol needs to happen in an agreed-upon manner, so stakeholders (and core developers) don’t get hit by surprises. All parties have a right to know beforehand how issues will be resolved.

Future blockchains need built-in governance systems. Whenever possible, decisions should happen on chain, not on Reddit or Twitter or some off-site polling tool. And, as part of that governance system, blockchains also need a testnet, so stakeholders can review protocol changes before implementing them.

But whether upgrades happen on the blockchain or off, the decision-making process needs to be clear, accountable and decentralized. The fact that the post-DAO fork was none of these is what will cost Ethereum in the long run.

This guest post is by Kathleen Breitman, COO of Tezos (tezos.com), a new blockchain platform currently in development. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of Bitcoin Magazine.