“Go for the Jugular” is the advice George Soros gave to his team during his famous attack on the British pound for a profit of $1 billion on so-called Black Wednesday in 1992. On October 15, 2018, tether, the market dominating stablecoin with a market cap of $2 billion, was attacked, breaking tether’s peg to USD, dropping its value by 7 percent but simultaneously driving up bitcoin and the whole crypto market by more than 10 percent. Even though nobody has claimed the attack yet, entrepreneurs, investors and customers of stablecoins should all carefully analyze existing and potential attacks and act accordingly.

Stablecoins, cryptocurrencies with stable value, are considered the “holy grail” of crypto since they could displace all the fiat money in the world which is about $90 trillion. As one might expect, investors have poured out hundreds of millions of dollars chasing stablecoin dreams, and, following the money, new stablecoin projects have come out left and right in 2018, which many have called the year of the stablecoin.

While there are many good articles on stablecoins, almost all of them focus on topics related to stablecoin design or why stablecoins are doomed to fail, and all analyses assume normal crypto market conditions rather than taking into account the volatile conditions we have experienced.

However, during an attack, the market movement is massive and sudden. Assuming these attacks are legal and highly profitable, just like Soros’ attack, they will come back again and again. Only the stablecoins that can survive these attacks can eventually become the “holy grail.”

Analysis of the Tether Attack

As of the writing of this article, there is not much information or data regarding the Tether attack on October 15, 2018. Who were the attackers? What was the method to profit from the attack? How profitable was the attack? What resources were required to execute the attack? Was there any attempt to defend against it? However, just by analyzing some limited public data from CoinMarketCap, we can gain valuable insights around these questions that are important in understanding such an attack.

First, the attack is a classical speculative attack: a massive and sudden selling of a currency during a relatively short period of time. Such an attack is usually executed by financial speculators; in this case, it is rumored that the recent Tether attack was mounted by IMMO.

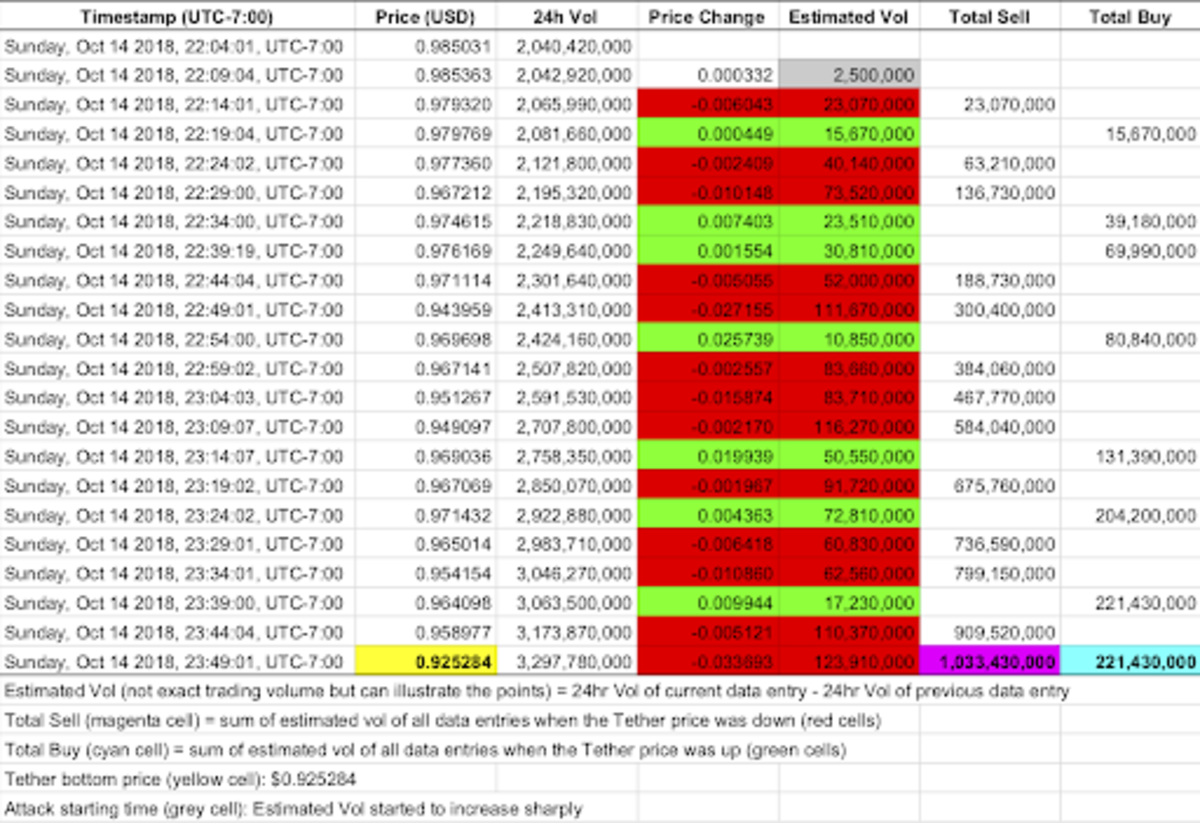

As shown in Figure 1, the whole attack was very short: only about three hours from start to finish. It started around Sunday, October 14, 2018, 10 p.m. PST (UTC-7:00) and finished around Monday, October 15, 2018, 1 a.m. PST (UTC-7:00). It took about 100 minutes to drive the tether price to the bottom at $0.925284. Then, about 65 minutes later, the price went back to $0.973513 and started to stabilize. The transaction volume during these three hours was about $2 billion, which was the average 24-hour trading volume around that period.

Figure 1: Tether’s 24-hour price from October 14, 2018, to October 15, 2018 (Source: CoinMarketCap)

Second, the method to profit from the Tether attack is actually different from the method used in Soros’ attack on the British pound. In Soros’ attack, shorting currency was used to generate profit: 1) First, Soros’ team built up a huge short position of pound sterling; 2) they executed a massive and sudden selling of the pound; and 3) they finally bought back the pound after breaking the peg, returned their borrowed pound and generated $1 billion in profit from the price difference.

In the Tether attack, it seems that the attacker(s) 1) first built up a big position in tether (either short or non-short position) and a big position in bitcoin or other crypto assets; 2) then executed a massive and sudden selling of tether, which drove the tether price down to the bottom and caused the bitcoin price to go up by about 10 percent; 3) finally sold the big bitcoin position to generate profit; and 4) possibly bought back tether at a lower price to reduce the loss from dumping tether.

I believe the attackers leveraged the fact that bitcoin and other crypto assets are perfectly negatively correlated with stablecoins. As shown in Figure 2, with about 15 minutes delay (CoinMarketCap only provided data in 5-minute intervals), the bitcoin price started to climb when the attack started, reached its peak when the tether price reached its bottom, and dropped as the tether price recovered.

Figure 2: Bitcoin’s 24-hour price from October 14, 2018, to October 15, 2018 (Source: CoinMarketCap)

Third, it is extremely hard to figure out exactly how profitable the attack was, given the limited data available. However, it is safe to say the attack was very profitable. Even though it does not let us determine the profitability of the attack, the whole crypto market went up 10 percent, adding $20 billion in value, while at the same time, tether dropped by about 7 percent, removing only about $210 million in value. That difference represents a tremendous opportunity for profit-taking.

Fourth, the effort to successfully execute the attack was huge but many people have the resources to mount such an attack. As a comparison, it took $10 billion short selling of the pound to break the peg; only Soros and a few others could have accumulated the resources needed in that attack.

As shown in Figure 3, if we assume the “Total Sell” volume was the capital required to break the tether peg to the bottom price of $0.925284 in ONLY 100 minutes, then it took more than $1 billion to achieve that. If we believe that there is a leverage in the market and that controlling 10 percent of the trading volume will move the market, then only about $100 million was required to start the attack and cause the market to follow.

Figure 3: Analysis of trading history during the Tether attack period (Source: CoinMarketCap)

Lastly, just as the British government tried to defend but eventually gave up defending against Soros’ attack, there was definitely an effort to defend Tether but it failed. As shown in Figure 3, if we assume the “Total Buy” volume was the effort to defend Tether, then the defender(s) spent at least $200 million, a huge amount that not many people can mobilize in a short 100 minutes.

What Are the Economic Incentives? Can a Project Defend?

Understanding the economic incentives for both attackers and defenders is critical to understand why attackers want to attack and how they attack, as well as whether defenders can actually defend the peg and whether they should even try.

The ultimate motivation for attackers to mount an attack on fiat currencies is economic gain. Who wouldn’t want to legitimately make $1 billion in profit as Soros did? The same motivation also holds true for attacking stablecoins. Stablecoin projects should recognize that breaking the peg is not the ultimate goal for speculators in mounting an attack. It is only a means to cause the expected market movements during the short attack period and profit from them accordingly, even though the stablecoins can return to the pegged price after the attack.

The key questions are whether attackers can design certain attacks that can generate financial profits or not, what resources are required to successfully execute the attack, whether the defender(s) have the capabilities to defend and whether they would be willing to defend or not. If there is a type of attack that is profitable, requires low effort to attack and cannot be defended, such a type of attack will come back again and again. Based on the above analysis on the recent Tether attack, the bad news for all stablecoin projects is that there is a profitable attack that requires low effort to execute successfully.

Some projects have argued that their designs can defend speculative attacks like Soros’ attack because there exists a large pool of “anti-Soros” speculators who can profit from defending the peg. But these arguments make the assumption that the attack will use the “shorting currency method” that Soros used.

This assumption will not hold if attackers use the method used in the recent Tether attack. During that type of attack, from a game theory point of view, speculators will generate more profit by joining the attack to further drive down the stablecoin price while at the same time driving up the price of bitcoin or other crypto assets, which will increase the spread when they return to sell the bitcoin at a higher price and buy back stablecoins at a lower price.

It seems the only party that has incentives to defend the peg is the project. Based on the analysis of the recent Tether attack, it requires a huge amount of capital in a short period of time to defend the peg. Unfortunately, none of the stablecoin projects today has the capital necessary to defend such an attack.

None of the stablecoin projects today can defend against a speculative attack!

Whether people like Tether or not, it should get some credit for attempting to defend the peg against the recent speculative attack. It spent at least $200 million to do so. It probably needs $500 million more to succeed in future attempts. More importantly, since these attacks happen during a very short period of time, there is no time to move money from the bank or issue bonds; therefore, the stabilization capital will need to be on hand, moving forward.

Some people argue that Tether is exiting the stablecoin business by retiring and burning tether. I would argue that Tether is actually moving capital from bank reserves to cash-on-hand (or at least attempting to reduce the reserve liability) so they can have a chance at defeating future attacks.

There Will Be More Attacks Than You Might Think

Fiat currency attacks are rare, even though a few of them have grabbed the headlines. Things are more complicated in the stablecoin market than in the fiat currency market. I expect there will be many more stablecoin attacks because there are more targets to attack, more types of attackers, more ways to profit, and more (and easier) ways to attack.

First, there are so many stablecoins projects — 60+ and increasing — and the majority of these stablecoins are competing for the USD-pegged market. Granted, most of these stablecoins have not reached the point where they are able to affect the market — many have not even launched yet. It won’t be a stretch to expect these will become targets for attacks sooner or later, especially since they all have some sort of design flaws.

Second, the attackers of fiat currencies are financial speculators who mount the attacks purely for financial profits. In the end, Soros cannot issue a new currency to replace the British pound as the fiat currency for England. In stablecoins, a project has strong incentives to attack and kill another project. Again, it is rumored that the recent Tether attack was mounted by IMMO which is developing a competing stablecoin. Likewise, an exchange has strong incentives to mount a stablecoin attack to steal traders from other competing exchanges, as we saw during the recent Tether attack when traders switched from tether-based exchanges to non-tether-based exchanges.

Third, there are limited ways to profit from a speculative attack on fiat currency. In addition to profiting from killing stablecoin competitors and stealing traders from other exchanges, financial speculators could profit from the sudden price rise of bitcoin and other crypto assets which are negatively correlated with stablecoins. And there could be more ways to profit that people haven’t even thought of yet.

Fourth, it requires a lot of capital to mount an attack on fiat currency and only a few speculators can secure that large amount. Soros amassed $10 billion for the famous British pound attack. The market cap of any stablecoin is still small and the ratio between fiat-inflow and crypto market cap is 1:50. Hence, it seems that a relative small amount of capital is enough to mount a successful attack. Due to some stablecoin designs, stablecoins can be attacked in ways that did not exist in fiat currency attacks, such as an oracle attack, which might even be easier.

Conclusion

As the recent Tether attack is written into history, I hope this can serve as a wake-up call for all existing and future stablecoin projects. When designing their stablecoins, projects should consider not only how the system will function in normal market movement environments but also the response strategy in extreme market movement situations when their stablecoins are being attacked. Only the stablecoins that can survive all attacks can become the “holy grail” of the crypto.

This is a guest post by Henry He. Opinions expressed are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of Bitcoin Magazine or BTC Inc.