Editor's Note: This is an opinion piece by Andrew Quentson; the views and opinions expressed are those of the author.

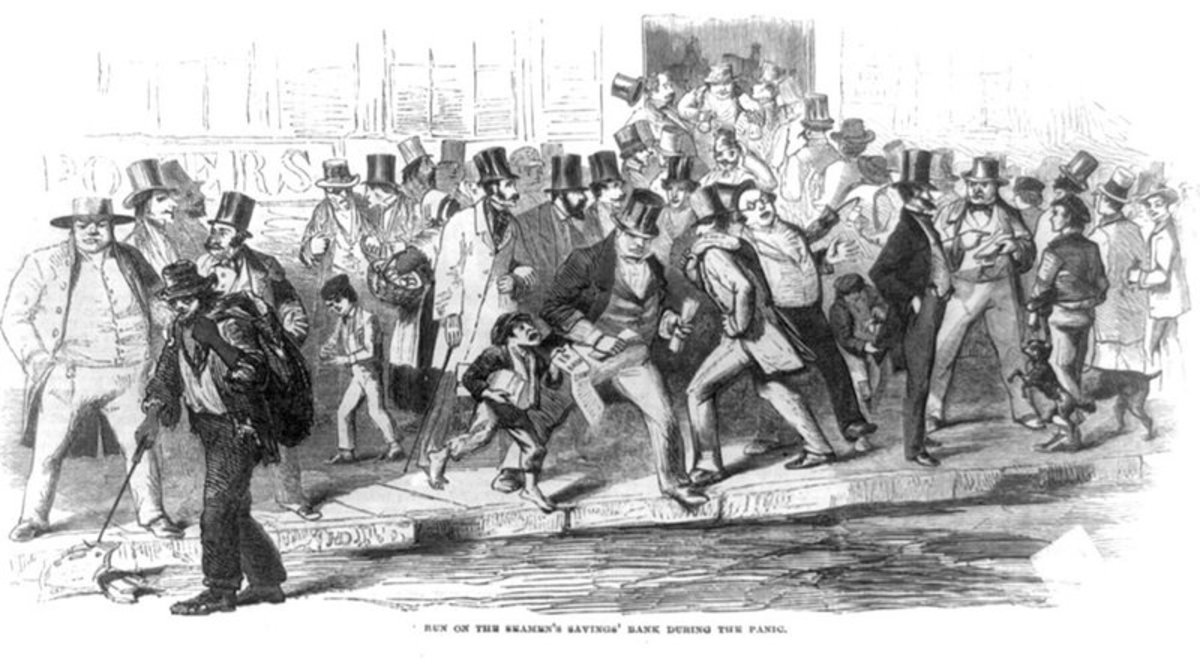

Since their inception, banks have been a systemic risk to the economic well-being of nations. Their crucial role in clearing, processing and creating money, the financial lifeblood of the economy, ensures efficient trade between specialized producers or service providers. Their failure to perform such a role would trigger national and global crisis, if not devastation.

The most recent example of such failure is the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in 2008 which triggered a chain of events culminating in some tense 48 hours when nations were “on the brink of catastrophe,” according to Hank Paulson, then treasury secretary, to such extent that “the former head of Goldman Sachs got down on one knee and begged [then-House Speaker Nancy] Pelosi” to support the $700 billion bank bailout known as the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). Meanwhile, Britain was “hours from collapse,” according to then-Chancellor Alistair Darling.

The effects of those fateful days are still reverberating. The cost to the United States is estimated in trillions, according to the U.S. Governmental Accountability Office. Directly or indirectly, the crises led to activist uprisings from both the left in Occupy Wall Street and the right in the Tea Party Movement – as well as riots in London in 2011.

If the West was hurting, the rest of the world was on edge to the point where revolution was underway in the Middle East and North Africa. That revolution, in parts of the world, turned to devastating war. The contagion spread to Europe, which at one point risked full collapse with vultures circling Italy, Spain and even France. Detroit went bankrupt. Greece, in an ongoing drama, was bailed out.

Everyone would like to prevent such systemic failures, that have sent some nations into deep recession and others into depression. While Occupy Wall Street pointed a finger at the “one percent,” the Tea Party blamed the government and the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission blamed everyone. It concluded that there were “widespread failures in financial regulation,” a “lack of transparency” with the up-to-the-hilt leverage “often hidden,” and there was “a systemic breakdown in accountability and ethics,” among other causes.

How the Monetary System Currently Operates

An often overlooked contributor to the crisis is the payment and monetary system itself, which is currently centralized into a few gigantic interconnected institutions that take on all risk to the point where they are now considered “too big to fail.” In a recent report, the Bank of England explained that these institutions create money “at the stroke of bankers’ pens when they approve loans.”

“Commercial banks create money, in the form of bank deposits, by making new loans. When a bank makes a loan, for example to someone taking out a mortgage to buy a house, it does not typically do so by giving them thousands of pounds worth of banknotes. Instead, it credits their bank account with a bank deposit of the size of the mortgage. At that moment, new money is created.”

Money is then destroyed when the loan is repaid, with the interest paid on the loan going toward the bank’s profits.

The report lists a number of constraints on banks’ ability to create money, such as demand for new loans, the interest rate set by central banks and risk of default. However, it acknowledges risk can be misjudged and such misjudgement “is sometimes argued to be one of the reasons why bank lending expanded so much in the lead up to the financial crisis.”

The report further states the interest rate is set by demand for central bank IOUs, rather than the other way around. Currently, such demand is almost non-existent. Therefore, central banks are, in effect, creating new reserve currency to keep inflation at 2 percent and encourage spending.

Arguably, as banks profit from new loans through interest, they are incentivized to create more and more money. Standards slowly relax, interbank competition kicks in, underwriting rules are ignored, complex instruments are created to both manage and hide risk, boom times arrive, while politicians take credit and assure everyone that there will be “no return to boom and bust,” as Gordon Brown, the Chancellor of the Exchequer for almost a decade, stated in 2006. The biggest boom and bust in living memory followed.

How the Current Payment System Works

Currently, most payments go through a centralized clearinghouse. The system itself is highly complex with many interconnections between clearinghouses, but in its simple form, when banks settle accounts between themselves, they rarely do so directly. They instead use a Central Counterparty Clearing (CCP) arrangement.

According to a report by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago:

“Through novation, the original contract between the buyer and seller is extinguished and replaced by two new contracts, one between the CCP and the buyer, and the other between the CCP and the seller.”

Otherwise stated, a clearinghouse acts as a “buyer to every seller and the seller to every buyer,” in the process taking on the risk of default by the buyer or the seller, which it can cover through margin requirements and other collateralization. For the service, of course, it charges fees or interest.

According to the report, clearinghouses “can be sources of financial shocks, such as liquidity dislocations and credit losses, or a major channel through which these shocks are transmitted across domestic and international financial markets.”

According to a speech by former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke at the 2011 Financial Markets Conference regarding the 1987 stock market crash:

“Surging volumes of trades and extraordinary price volatility during the week of October 19th created errors and delays in confirming stock trades, severe operational and financial stress at clearing members, and heavy liquidity demands throughout the financial markets. In the derivatives markets, multiple intraday margin calls were made to protect the clearinghouses, but banks sometimes delayed making key payments to and from the clearinghouses, adding to the uncertainty. Meanwhile, the clearinghouses themselves apparently absorbed significant amounts of intraday liquidity from the markets by collecting, but not always paying out, so-called variation margin ‒ payments that investors were required to make as the values of their holdings plunged.

In reviewing the episode, the Brady Commission noted that although the clearinghouse system avoided defaults, investor uncertainties about the viability of the clearinghouses, as well as about the ability of major broker-dealers to meet their obligations, intensified market fluctuations and panic.”

Concerns have been raised that far too much risk is placed on the clearinghouses which manage hundreds of trillions of dollars.

"What happens if they go bust? I can tell you the simple answer: mayhem. As bad as, conceivably worse than, the failure of large and complex banks," Paul Tucker, Deputy Governor of the Bank of England, said in October. The Economist says that a regulator privately described them as “too big to fail, on steroids.”

Sometimes they do fully crash for a short period. The worry, however, is failure to manage risk which may lead to a counterparty default, forcing CCPs to dip into their reserves. If they are unable to meet their obligations then the risk passes on to banks. Depending on the magnitude, it could be trillions of dollars and a collapse too big to bail.

Enter Bitcoin and Blockchain Technology

“When everything else is stripped away, the most pressing issue is the management of risk.” ‒ from the 1987 crash report of the Hong Kong Securities Review Committee.

Although many have tried to impose their utopian ideologies on Bitcoin, in its foundation the technology is rather dull and boring. It concerns not governments or banks, but risk and risk management. Instead of having a counterparty or an intermediary, Bitcoin allows direct payment in an unforgeable, immutable trivially verifiable way.

Bitcoin not only minimizes risk, but eliminates it altogether. It has an inbuilt clearinghouse through the use of mathematical proofs which allow transactions to be chained to one another in a blockchain in such a way as to make fabrication of a bitcoin or Bitcoin transaction impossible. Accounting, therefore, is simplified. Transactions are as good as instant. Complexity is almost non-existent. It takes the whole monetary and payment structure and simplifies it in such an outside-the-box way that it makes one wonder why on earth we did not think of that before.

In a recent editorial, CFTC Commissioner J. Christopher Giancarlo, calling on regulators to employ a “do no harm” approach, highlights the inefficiencies of the current system by going back to those fateful days:

“Trading conditions were deteriorating by the minute. It was clear that the regulator had little means, short of telephone calls, to read all the danger signals the market was broadcasting.”

Bitcoin’s global ledger is pseudo-anonymous. That is, it can be as private or as transparent as one desires. It keeps a record of all transactions for eternity, but whether that transaction is attributable to an entity depends on the entity itself. If one does not reveal ownership of a Bitcoin address, it is difficult to attribute ownership. If, however, one does reveal it, a historical record is kept forever, thus making it difficult, if at all possible, to hide or fabricate the past. While in 2008 institutions lost track of who owns what, thus creating mistrust and a freezing of interbank transfers, in Bitcoin it is quite easy to prove ownership if so desired.

Of course, the technology itself is not without problems and, unlike the claims of some, it is not a solution to complex issues of governance or lending; it is simply a technology which allows for value transfer in such a way that risk is minimized, if not fully eliminated. While some of its implications are as far-reaching, if not more so, than the Internet itself in democratizing finance, the invention is an incremental improvement and a product of decades of research.

From a technological point of view, Bitcoin is the most exciting invention since the Internet. While previously the smartest brains on the planet where focusing on creating yet another cat picture-sharing app, now they are working on more efficient, more secure, less risky value transfer and, in the process, improving trade and increasing wealth.

From smart contracts to the Internet of Things, an era of automation in finance is underway. This new technology brings to the world a 21st century financial system where money is simply permissionless information which can travel at the speed of light from London to New York and Shanghai.

It took seven years, but the regulators and the CEOs have now seen what some parts of the community hid under their utopian rhetoric. A world race is underway to catch the low- hanging fruit and become, perhaps, the first trillion-dollar company with savings in billions promised and new opportunities opened.

Sources:

https://next.ft.com/content/8090cc80-fff6-11e5-99cb-83242733f755

Bank of England Payment System Crashes

http://www.reuters.com/article/clearing-default-idUSL6E8CD4AL20120116

http://www.economist.com/node/21552209

https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/bernanke20110404a.htm

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OU_fzCpwrNc

http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-13-180

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2008/sep/27/wallstreet.useconomy1

http://news.bbc.co.uk/today/hi/today/newsid_8914000/8914062.stm