This is an opinion article by Guglielmo Cecero, the legal manager of European bitcoin investment app Relai, and Raphael Schoen, the content lead at Relai.

Bitcoin is under attack. It is increasingly seen as a “dirty currency.” Elon Musk’s Tesla, Wikipedia, Greenpeace and other organizations have stopped accepting BTC for their products or as a means to donate money.

Musk, who is not only one of the richest but also one of the most controversial people on this planet, has said: “Cryptocurrency is a good idea on many levels, and we believe it has a promising future, but this cannot come at great cost to the environment.” Ouch.

And it’s not just Musk. Politicians have also taken aim at Bitcoin.

Before the European Commission’s Markets in Crypto-Asset Regulation (MiCA) regulation was passed, it caused quite a stir within the Bitcoin community, especially due to the left-wing factions of the EU Parliament that were opposed to proof of work (PoW) and the power consumption of the Bitcoin network. In the trilogue, a version of MiCA was finally passed that did not ban PoW or mining.

As became known in April 2022, some members of the European Parliament (MEPs) tried to push through a ban on bitcoin mining and one on BTC trading in the course of the draft law. Luckily, they failed.

However, the foundations for further steps have been laid. For example, the issuers of cryptocurrencies, which we know are mostly simply tech startups, will be obliged to deliver some kind of report on the energy consumption and the associated carbon footprint of the respective asset. Brokers and exchanges, in turn, must inform their customers about these exact figures when they purchase crypto assets.

The increasing aversion to Bitcoin also gained traction through an anti-Bitcoin Greenpeace USA campaign launched in March, which was financed by Ripple co-founder Chris Larsen, among others. Interestingly, Greenpeace accepted bitcoin donations between 2014 and 2021 until they were put on hold due to environmental concerns.

Nearly Half Of The EU Parliament Doesn’t Like Bitcoin

As mentioned, a mining or trading ban for Bitcoin didn’t make it into the MiCA legislation. However, it is very unlikely that members of the EU parliament who tried to implement this in MiCA will give up — we can assume the contrary.

In March 2022, the economic and monetary affairs (ECON) committee in the EU parliament voted against a ban on PoW. Thirty-two members voted against it, 24 in favor. The topic seems to become more and more ideologically driven, as the Social Democrats, the Greens, and the left mostly wanted a PoW ban, whereas the Conservatives, the Liberals and right-wing factions tended to vote against it.

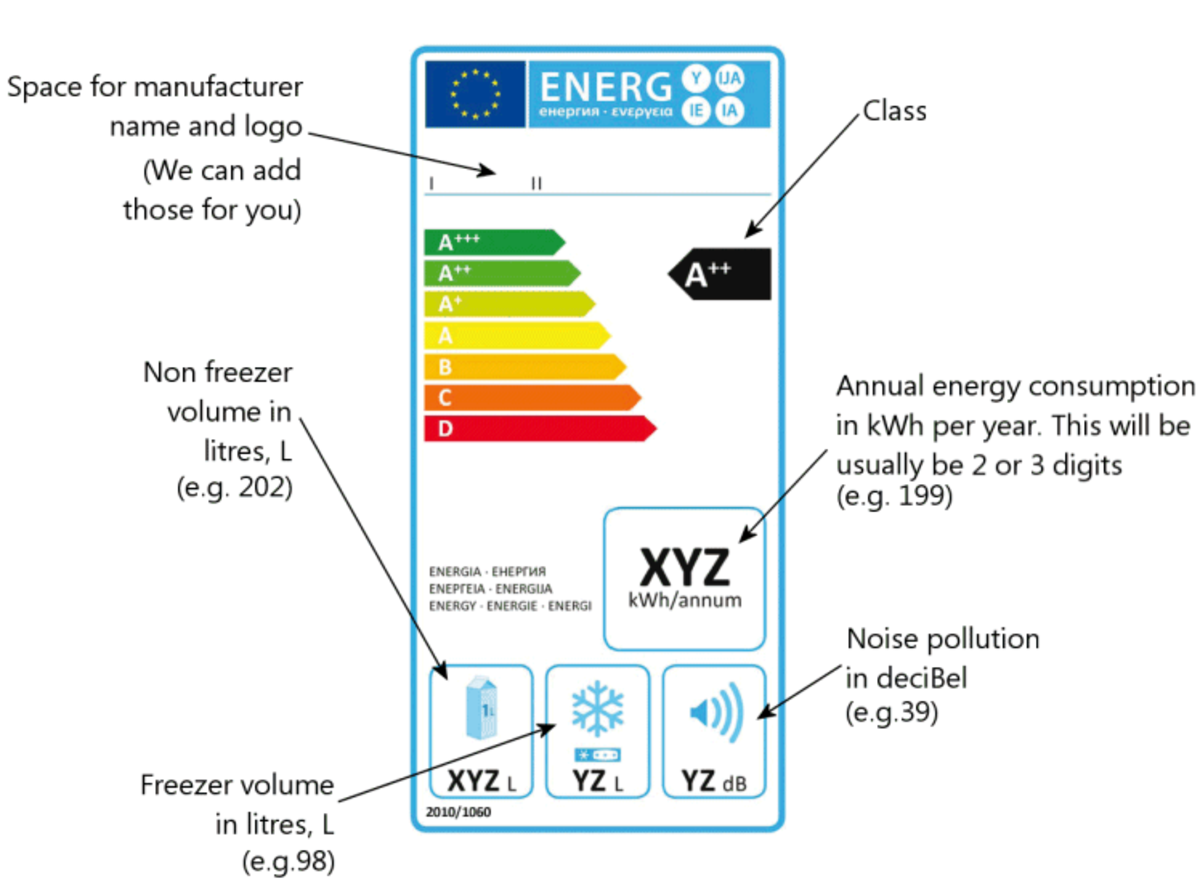

The final MiCA draft created by conservative MEP Stefan Berger included a compromise: Instead of a ban on PoW, they agreed on including a rating system for cryptocurrency to assess their environmental impacts (more on that later).

In an email conversation with Politico, the Spanish Green EU parliament member Ernest Urtasun explained:

“Creating an EU labeling system for crypto will not solve the problem as long as crypto-mining can continue outside the Union, also driven by EU demand… The Commission should rather focus on developing minimum sustainability standards with a clear timeline to comply.”

And he added:

“Ethereum’s recent upgrade just showed that phasing out from environmentally harmful protocols is actually feasible, without causing any disruption to the network.”

The ECB Doesn’t Like Bitcoin — At All

While we see different opinions on Bitcoin in the European Parliament, the signals we’re getting from the European Central Bank (ECB) are very clear. The ECB is issuing warnings about cryptocurrencies on a regular basis, naming their “exorbitant carbon footprint” as “grounds for concern”.

Just recently, on November 30, 2022, the ECB published a blog post titled “Bitcoin’s Last Stand.” In it, ECB’s Market Infrastructure And Payments Director General Ulrich Bindseil and advisor Jürgen Schaff argue that, “Bitcoin's conceptual design and technological shortcomings make it questionable as a means of payment.”

According to Bindseil and Schaff, Bitcoin transactions are “cumbersome, slow and expensive,” which they say explains why the world’s largest cryptocurrency — created to overcome the existing monetary and financial system — "has never been used to any significant extent for legal real-world transactions.” Bindseil and Schaff added that since Bitcoin is neither an effective payment system nor a form of investment, “it should be treated as neither in regulatory terms and thus should not be legitimized.”

While it may seem paradoxical to very vocally attack something that is on the “road to irrelevance,” it is not the first time that the ECB has attacked Bitcoin.

In July 2022, the ECB singled out Bitcoin in a research article and compared proof of work to fossil fuel cars while considering proof of stake as more akin to electric vehicles. Let’s ignore for a minute that this doesn’t make sense and look at what it wrote in detail:

“Public authorities should not stifle innovation, as it is a driver of economic growth. Although the benefit for society of bitcoin itself is doubtful, blockchain technology in principle may provide yet unknown benefits and technological applications. Hence, authorities could choose not to intervene with a view to supporting digital innovation. At the same time, it is difficult to see how authorities could opt to ban petrol cars over a transition period but turn a blind eye to bitcoin-type assets built on PoW technology, with country-sized energy consumption footprints and yearly carbon emissions that currently negate most euro area countries’ past and target GHG saving. This holds especially given that an alternative, less energy-intensive blockchain technology exists.”

In general, the ECB believes it’s highly unlikely that the European Union will not take action in terms of carbon emissions on PoW-based assets like bitcoin. The authors of the paper argue that in their view it’s likely that the EU will take similar steps on phasing out PoW as they are doing with fossil fuel cars. Especially since, according to them, an “alternative, less energy-intensive” technology like PoS exists.

“To continue with the car analogy, public authorities have the choice of incentivising the crypto version of the electric vehicle (PoS and its various blockchain consensus mechanisms) or to restrict or ban the crypto version of the fossil fuel car (PoW blockchain consensus mechanisms). So, while a hands-off approach by public authorities is possible, it is highly unlikely, and policy action by authorities (e.g. disclosure requirements, carbon tax on crypto transactions or holdings, or outright bans on mining) is probable. The price impact on the crypto-assets targeted by policy action is likely to be commensurate with the severity of the policy action and whether it is a global or regional measure.”

The vast majority of citizens are used to thinking of money as something other than what it really is, and the ECB is also to blame for this. Money is perceived as something that has value by itself, instead of something whose value comes from the interaction between the people who use it.

The euro is subject to both constant changes (regular inflation) and traumatic events (devaluations, forced exchange rates, etc.), but these are ignored or otherwise underestimated. People believe they own it, although they can only exchange it for other things.

For how many and for what things will 100 euros be exchanged in one year, five years or ten years? This is, in no way, up to us.

Its exchange function is constantly changing due to factors we cannot control. The interaction between those who use it is the main factor and, in turn, this interaction depends on economic and monetary policy rules that few people know about.

Bitcoin escapes these rules (and this is the reason why the ECB wants to ban it), it is just code that the ECB and the regulators are trying to make useless. Bitcoin also and above all expresses its value through features that are totally independent of a government’s power and, therefore, the ECBs.

What Will Happen Next?

In 2025, we will see a rating system for cryptocurrencies according to their environmental impact within the European Union — think energy labels for fridges or TVs. You can already expect that bitcoin will get the worst classification. This step will essentially be positive for Ethereum and bad for Bitcoin.

It’s quite unlikely that such a label will scare off investors from buying bitcoin, especially since the Bitcoin community is saying that the Bitcoin network is not an obstacle but a solution for more green energy.

Therefore, the Bitcoin mining industry has the incentive to become greener: The fossil fuel analogy in the ECB paper makes no sense. The energy mix of a PoW network like Bitcoin can come entirely from renewable, green sources. Bitcoin can serve as a way to immediately monetize energy, as is already happening with flared gas that would be flared anyway. However, it’s questionable how fast and effective this effort will be to policymakers, especially since fossil energy companies like Exxon are now mining Bitcoin using flared gas.

The authors of the ECB paper are already implying that a higher bitcoin price equals more energy consumption, as more miners will participate. Destroying demand for bitcoin would hence be an effective solution to bring down the hash rate. At least in theory.

Conclusion

The academic and political consensus seems to point toward something like trying to retire the “old” PoW, and moving towards the “new” PoS standard. Particularly since Ethereum’s recent merge, many bystanders believe this could be a viable path for the Bitcoin network. We doubt that and plan to elaborate on that in a future post. As we’ve seen in different scenarios, banning Bitcoin is hard, if not impossible. The Nigerian government tried, failed and eventually gave up, for instance.

It will be quite a while until 2025, and with an energy crisis, increased focus on carbon emission as well as global uncertainty overall, the only thing we can do at this point is to expect the unexpected.

Even if the worst-case scenario happens, and we see a Bitcoin ban of some sort happen in the EU, we doubt that this will hold forever. Bitcoin does not ask for permission. Bitcoin is something that ontologically struggles to stay inside a fence. It is not an idea derived from anarchist positions, it is an argument derived from the inherent characteristics of the technology introduced by Satoshi Nakamoto. The regulators work in an authorizing logic and so it is clear that they struggle to intercept the Bitcoin phenomenon, which functions regardless of someone else’s permission.

This is a guest post by Guglielmo Cecero and Raphael Schoen. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.