TXID: cdd8014a379a8731fc9e9ba1fef8954ccda9e8300356c6f198144dee11bcdd36

We would like to think of ourselves as masters of technology. We are the craftsmen, practitioners and creators. This assumption underpins many of our accepted models for understanding history. It’s a comforting way to view the world, with humanity and its heroes as the authors of our destiny. What is a far more uncomfortable truth is that technology equally creates and influences us, and molds the collective behavior that we call culture.

The invention of agriculture made the town the primary social unit, while the mass production of the automobile created cultures of independent holiday makers, commuters and suburbs. Every time Spotify autoplays a new song, when you visit a new restaurant based on its Yelp rating, Tinder’s algorithm displays or does not display you a potential date or a QR code allows health agencies to track and mandate the movements of individuals in a pandemic, technology is influencing culture.

Our choice of technologies - the appliances we use, the cars we drive, the operating systems we choose and the social media platforms which we engage in discourse on shape our lives by what they accentuate and what they hinder, defining the range of actions that are acceptable or prohibited. Technology is not only how human beings sculpt the world in their image, but in framing and defining the range of actions that are possible and encouraged, technology also sculpts who we become.

Producing paper is vastly more efficient than producing parchment, which requires around 200 animal hides to create a single book. Source 1, Source 2

The Qur’an says that good Muslims should seek knowledge, and as a consequence, mathematics, science and engineering flourished in Eastern antiquity. Cultural attitudes led to the invention of paper, which allowed information to be recorded far more efficiently and easily than with papyrus or parchment, which was the popular medium in Europe, where many kings remained illiterate up to the thirteenth century. Our choice of technologies is prescriptive of our character, how others perceive us, and ultimately our destinies.

Yet however potent a technology may be, it ultimately requires a user to be motivated to activate it, to switch it on, to use it, and that user will use it in the manner that they see as most aligned with their beliefs, their will and their intention, and how they see themselves reflected in it. In this sense all technologies are first and foremost tools for individual self-actualization, expression and exploration, a window or framework to understand who we are.

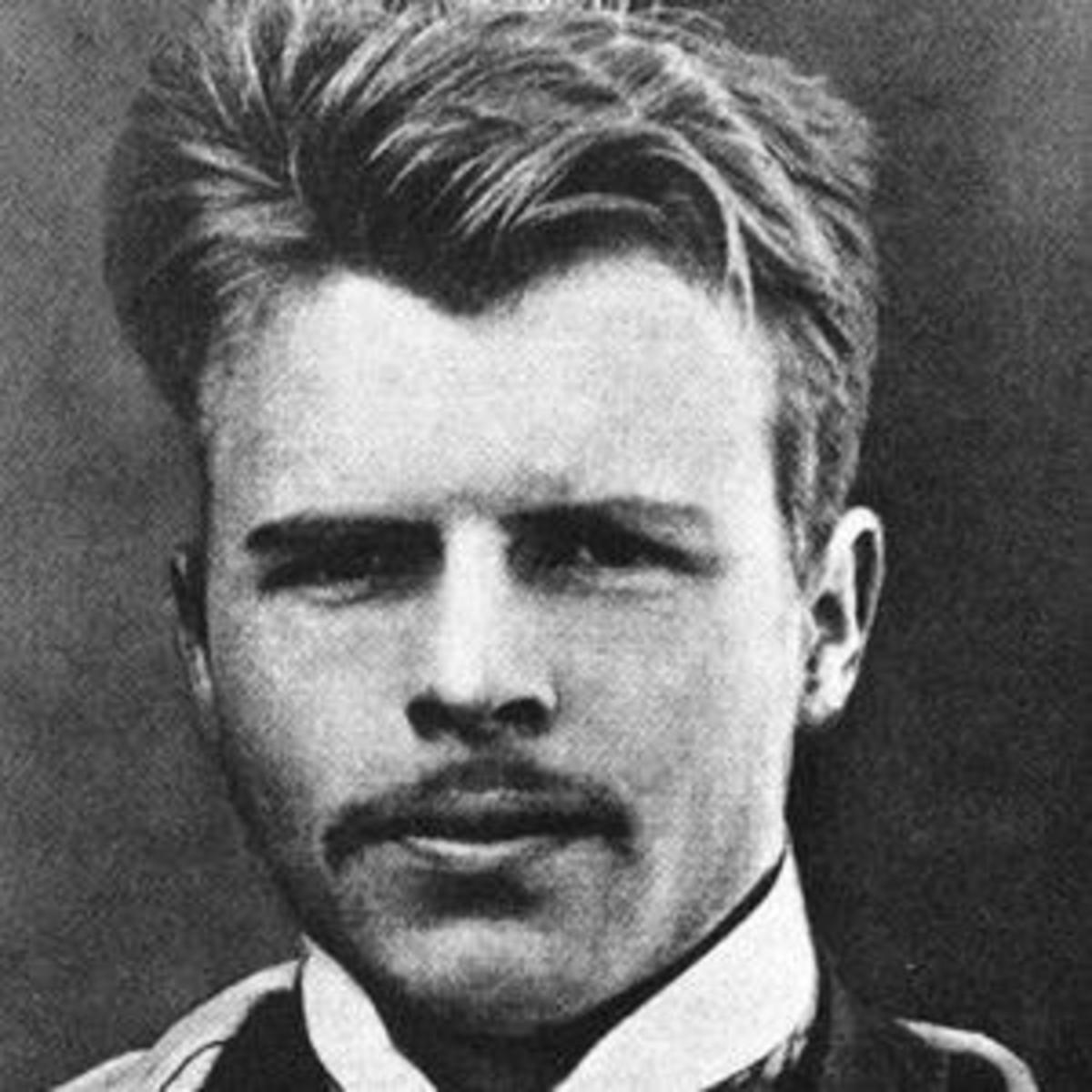

Hermann Rorschach was a Swiss psychologist born in 1884, Zurich, Switzerland. Known to his school friends as “Klex,” due to his enjoyment of klecksography, a child’s game making elaborate pictures from inkblots. As a young adult, he was torn between following his father into the arts or a career in science. He eventually settled on medical school where he majored in psychology.

During his studies, he came across the work of psychiatrist Szyman Hens who had experimented with using inkblots to study the fantasies of his patients. Rorschach saw the opportunity to combine his interest in the arts and the emerging field of psychoanalysis.

After much research and experimentation, he settled on a set of inkblots and a system for scoring the responses to them. He published what has come to be known as the Rorschach test in his 1921 book “Psychodiagnostik.”

Hermann Rorschach

The test itself is administered by presenting the subject with 10 cards in turn and asking them “what might this be?” It’s made clear that there are no right or wrong answers, the subject can pick up the card and view it from any position or orientation they desire, and they’re free to interpret the image however they want. The goal is for them to verbalize what the image suggests to them, with total freedom. Following this the examiner reads the subject’s responses back to them and asks the subject to clarify or elaborate where necessary, not to elicit further information but simply to ensure they have sufficiently accurate information to accurately score the test. The objective is to establish what is being perceived, where it is in the inkblot, and how particular inkblot features contribute to or help determine the response.

The subject’s responses are then used to determine a scoring on several metrics via a complex coding system. The scoring is not based primarily on what the individual says they see in the inkblot. In fact, the contents of the response are only a comparatively small portion of a broader set of data including response times, remarks and comments unrelated to the test, the originality or lack of originality of the responses, and the emotions, attitude, and frame of mind of the subject.

The Rorschach test takes a common stimulus and uses it as a context; the conscious and unconscious reactions of the subject towards that context are data points to better understand their mind.

Earlier we elaborated on how the context provided by a “thing” influences what we create or express, and the way we choose to use it is an act of self-exploration, i.e., it reflects who we are and what we will become. Rorschach similarly understood that by using the context of a fixed set of images and recording the wildly different interpretations created by an individual’s imagination in reaction to each, we could gain insight into a person's mind, and how they were likely to behave in the future.

It is human nature that we can’t help but to project our imaginations onto a thing, and these things, whether they be an inkblot on canvas, an automobile, or a computer program provide context, framing and boundaries for the expression of that imagination. This combination of imagination and framing decides how we act, and over time, what we become - our destiny.

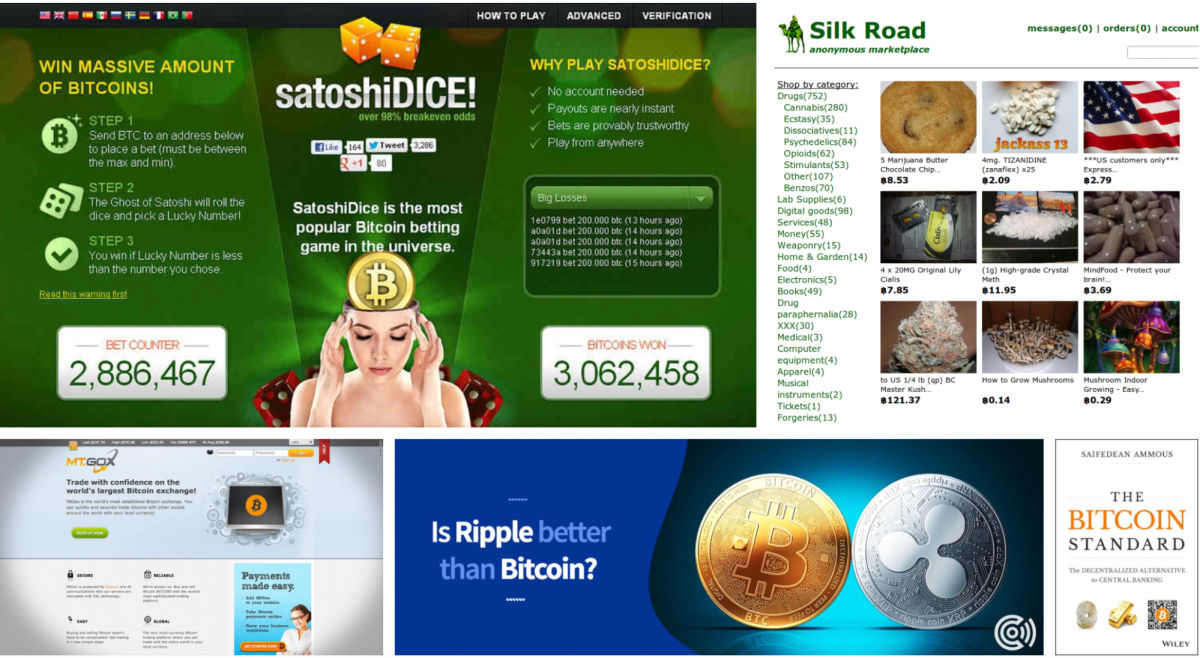

Since Bitcoin’s invention people have debated what it really is — a peer-to-peer payments system, a form of digital gold, anonymous digital cash, a censorship-resistant means of transmitting value, an immutable ledger of data, the first primitive prototype of a new computing technology called the blockchain, a craze to speculate on, a Ponzi scheme, a tool for extortionists, drug dealers, terrorists and pedophiles? What is Bitcoin?

From Satoshi’s whitepaper, to early discussion on the Bitcointalk forum and the cypherpunks mailing list, to Laszlo Hanyecz’s purchase of a pizza, through the drama of Mt.Gox and Silk Road, and the explosion of other copycats or newcomers looking to be “like bitcoin but with x”, the common perceptions of what bitcoin is and what it means have changed since its inception. Today the popular consensus seems to be that bitcoin is a type of hard money, or digital gold. In five years, with the proliferation of technologies on Layer 2 and beyond like Lightning (that enables a word of utility anchored on the ultimate truth of the Bitcoin blockchain) it's quite possible that this popular consensus will be something altogether different.

In truth Bitcoin is all of those things and it is none of them. It’s just code. Ultimately someone has to run that code, to mine the blocks, to send and verify the transactions. Their collective actions decide what Bitcoin is. Anyone could fork the open-source code and decide to raise or lower any value, that this or that is valid or invalid, defaulted on or defaulted off, or even increase the supply or issuance. If a sufficient majority of users agree to mine, verify and transact based on that code, this is Bitcoin, at least by the most objective measures possible.

More importantly though, how users collectively decide to act within the boundaries of what is permissible within this chaotic consensus defines what Bitcoin really is, defining its impact on the world and on our lives. Although the code provides an incorruptible, predictable source of truth, the ramifications of that truth are profoundly different in a world where all bitcoin is held by large banks, governments and corporate treasuries and therefore the legal regulations, political reality, societal norms and cultures of compliance dictate the average person interacts with it in a permissioned fashion, much like the legacy banking system. This would be a much different reality than an alternative where every user uses their own full node as a source of truth, holds the keys to their coins and makes informed decisions on the software they run based on its benefits for privacy and self-sovereignty. The aggregate state of affairs that emerges from these actions and values determines what Bitcoin actually is, not the software, or the network, but what it means for the world around us.

“Bitcoin” the network (capital B) and “bitcoin” the asset or currency (lower-case b) are in fact two separate (though highly-interrelated) things. They can exist without each other. For example, if there was an unprecedented worldwide internet outage the network would halt, transactions and blocks would cease to be broadcast, but the ledger itself would remain unchanged. Likewise the Bitcoin peer-to-peer network can broadcast messages and seek to create a global network of connected computers, without any blocks or transactions needing to take place. There exists a third completely separate thing from Bitcoin the network or bitcoin the currency, Bitcoin the idea.

Bitcoin the idea is like the Rorschach test, a particular interpretation of a thing, based on an individual’s experiences, personalities and biases, dreams and fantasies. Your ability to influence the ledger is limited by your financial means divided by the market cap of bitcoin; your ability to influence the network itself even more negligible, determined by the software implementation you run, the parameters you choose and the infrastructure you deploy — all of which must be largely in lockstep with the majority of the network. But your ability to influence Bitcoin the idea is where you have the greatest agency, to answer the Bitcoin Rorschach test, to decide individually what Bitcoin the idea is, and what you will do with it.

Without the robust software, the hash power, the businesses and the products and services that build out the network, Bitcoin the idea is little more than a kumbaya Ponzi scheme which a top-knotted 30-something influencer would shill you on Instagram. Equally it is true that without the recognition of Bitcoin the idea, bitcoin the currency would have no value: there would be no hash power, no nodes, no ecosystem, and the economic incentives that today secure it against almost any conceivable attack vector would not exist. Although it may seem inconceivable now remember that for several years Bitcoin existed in a form largely identical to what it is today, with almost all the value propositions of the technology and protocol we know today but had no value, or it was traded for loose change. It is not the technology itself that increased its value, it was the collective recognition of its brilliance, the growth of Bitcoin as a meme is what led to there being any price, let alone the prices, ecosystem and the hash rate we have today.

No one can own a culture, they are the collective possession of its participants.

We are here because people see themselves in Bitcoin; they will project their values, their hopes, their aspirations, whatever they want the world to be, onto a technology, onto Bitcoin. A sound money, a way to make more of your chosen fiat currency or buy a Lamborghini, a way to buy drugs, a way to make payments that otherwise are prohibited or impossible, a social club to meet people, a way to sound smart and impress people on the internet, an interesting technology, a way to get a job, a way to provide a nest egg for their children, a ray of hope in a dystopian world. It doesn’t matter, Bitcoin is all of these things and none of them, what matters is how its users use it.

Bitcoin is not a centralized service but a peer-to-peer network and state of affairs controlled by its users despite their disparity of views. Anyone can download it, anyone can fork the software or contribute code, there is no CEO of Bitcoin, it has no official website or spokesperson. Bitcoin has more in common with punk rock music or Rastafarianism, or Oaxacan tradition than a centralized top-down entity like Spotify, Tinder, or something owned by a government agency or a corporation. No one makes the rules in Bitcoin, we all do. Bitcoin is solely the possession of its community of users. Bitcoin is a culture, Bitcoin is a meme.

“Birds of a feather flock together.”

People stared at the inkblot of Bitcoin and acted on what their imagination showed them. Bitcoin itself is simply the aggregate actions of thousands of these otherwise-unrelated individuals participating in a network because their imagination told them it is of benefit to their own ends to do so.

Bitcoin is living technology, an economically self-sustaining culture, the aggregate sum of all its users, who participate because they see themselves in Bitcoin. Without them, it is simply another repo on GitHub.

This is a guest post by CoinsureNZ. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC, Inc. or Bitcoin Magazine.