The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is auditing companies who registered with the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) as a Money Service Business (MSB) involved in the Bitcoin space — it’s called a Title 31 Exam. These exams were once typically reserved for Indian Casinos but they're happening in the Bitcoin space now. I’ve seen a few companies get hit with these exams last week and from what I've heard, they've been issued en masse, rather like the SEC subpoenas of early 2018. It's an unpleasant notice to receive. The far-reaching rules of the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) apply equally to companies with large resources and small-scale bitcoin ATM operators or exchangers.

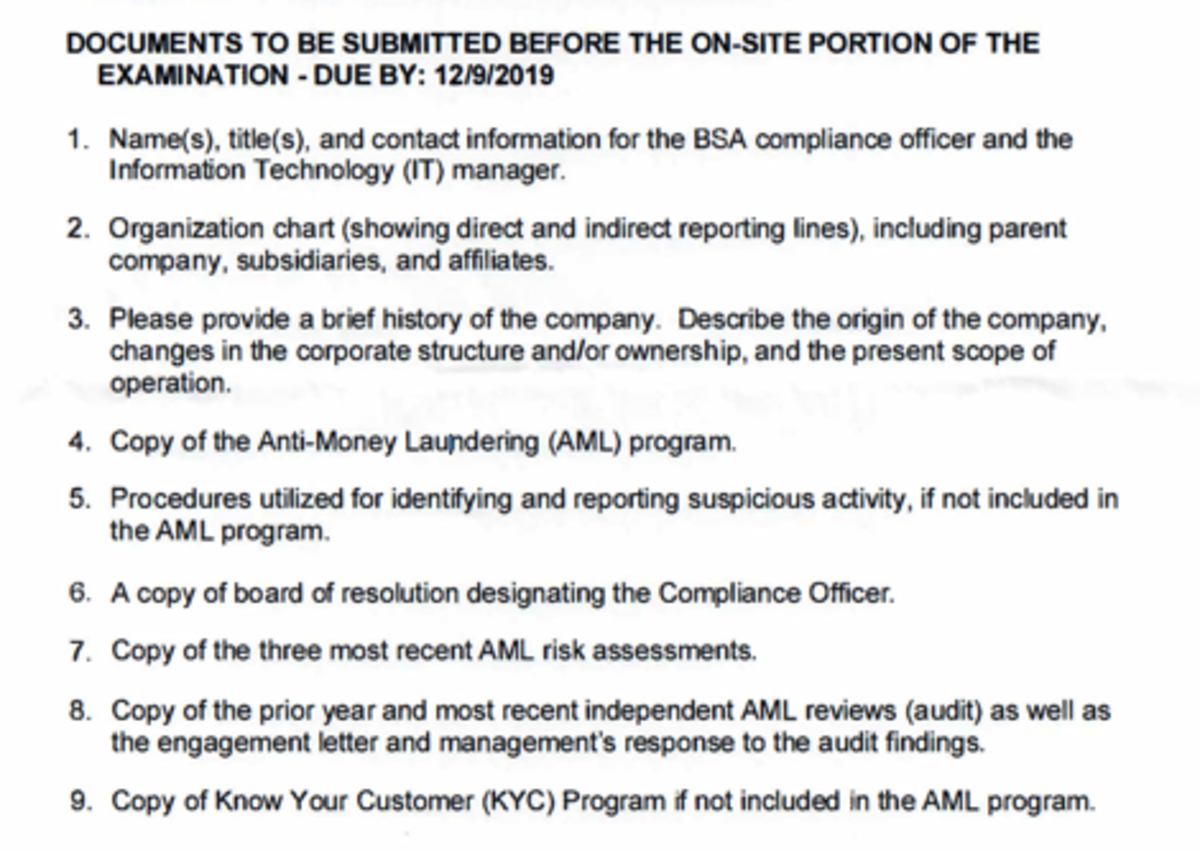

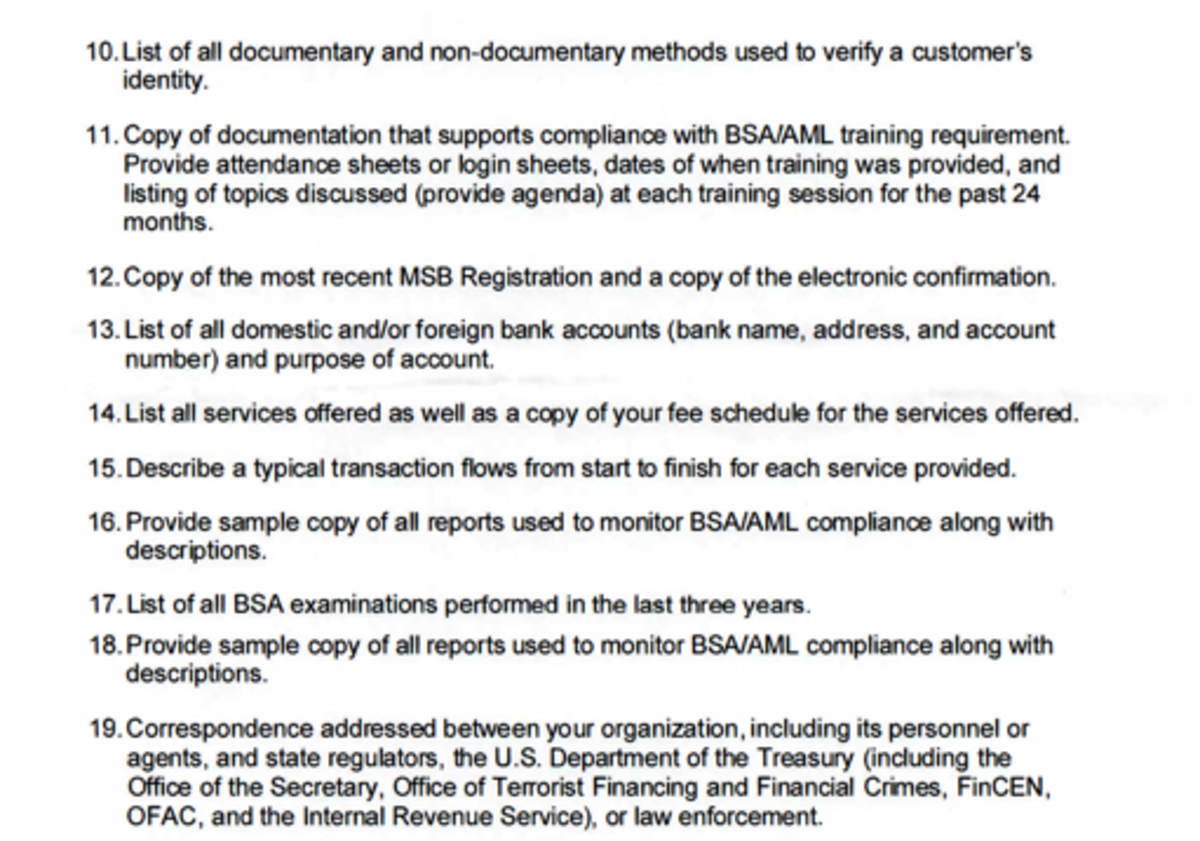

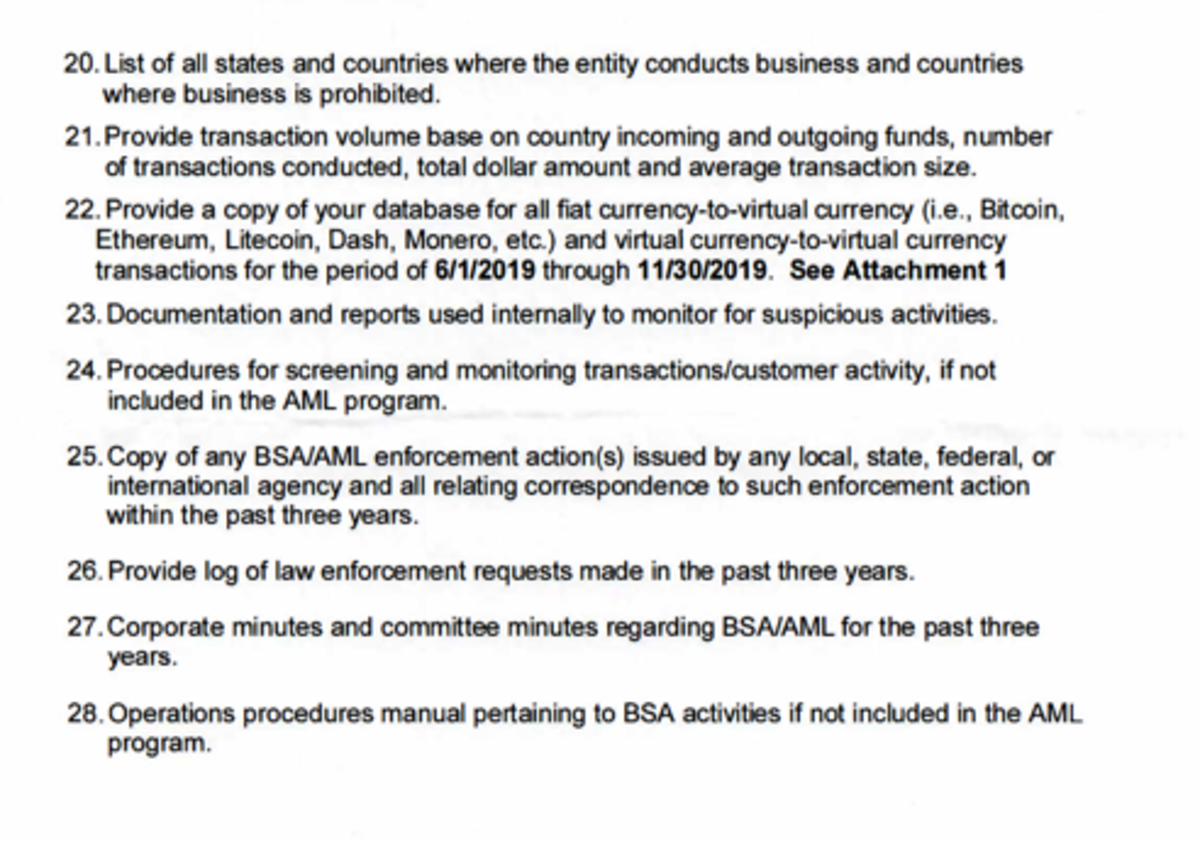

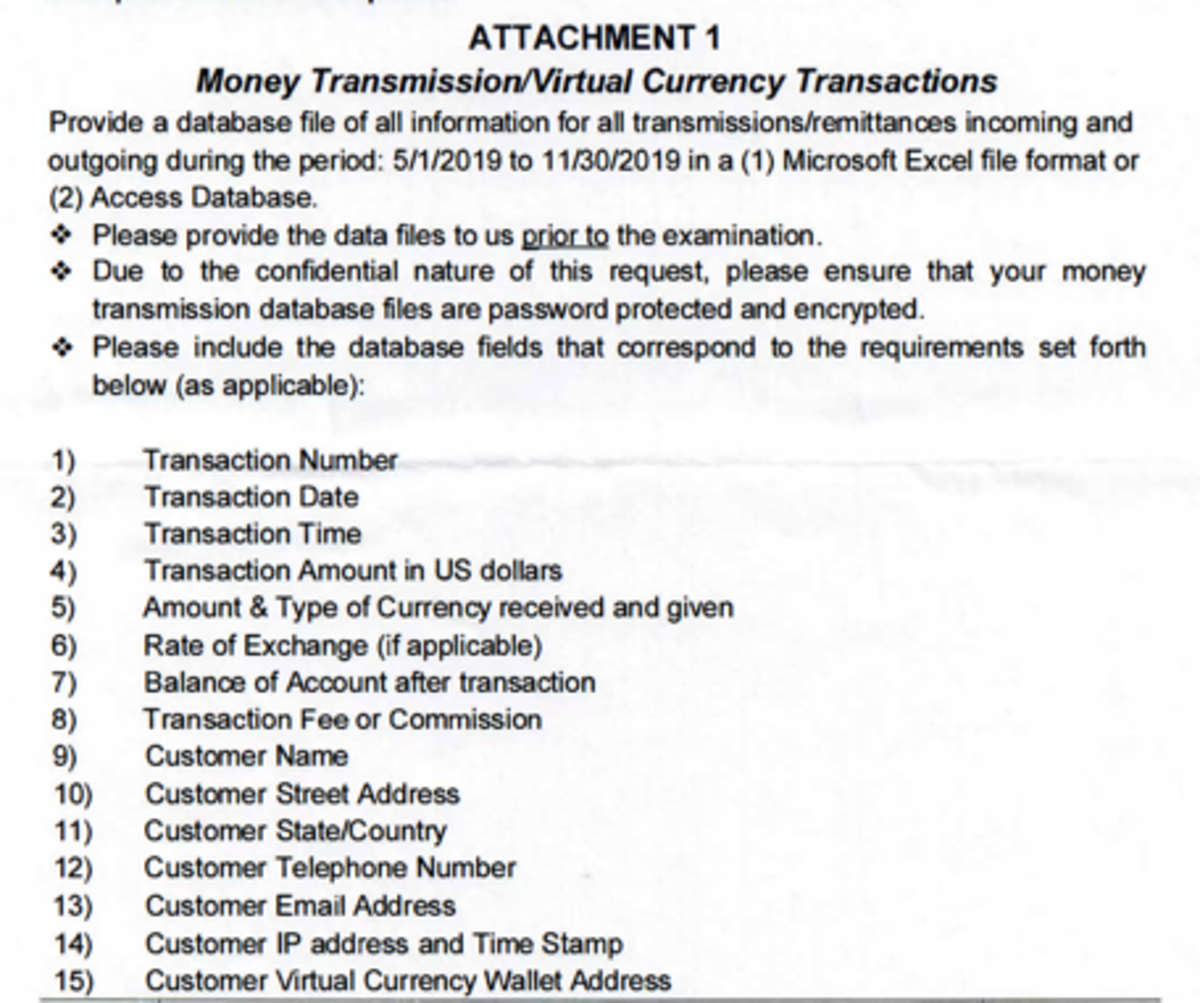

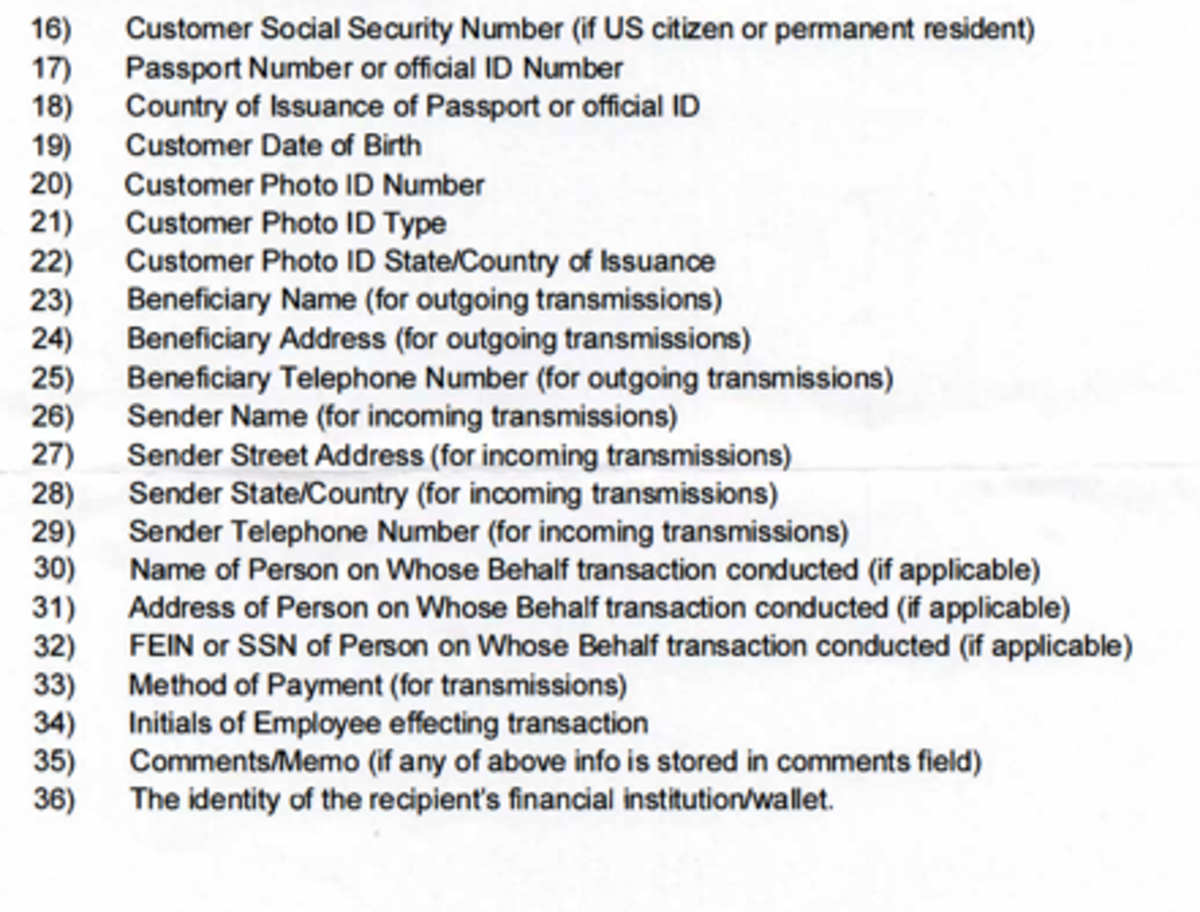

The notice tells the MSB company that the IRS is coming in person to ensure the MSB complies with the BSA. They are picking a four-month range and examining all transactions that have taken place within the specified dates. This is not an income tax audit, but the notice makes sure to point out that the recipient may be liable for penalties if they have failed to comply with the BSA.

Registration as a Money Service Business

It all feels like an attack on the fungibility of bitcoin, but no matter a company’s views on privacy, the reality of the situation is this: If you exchange or issue cryptocurrency as a business in America, you are required to register as an MSB and comply with the Bank Secrecy Act. These steps require

- Hiring a compliance officer;

- Registering as an MSB with FinCEN;

- Drafting a robust Compliance Program including an AML Policy, OFAC Policy, KYC Policy, Customer Identification Policy, Enhanced Due Diligence Policy, SAR Policy, CTR Policy, Record Retention Policy, Independent Testing Policy, and Staff-Training Policy; and

- Following the policy.

Based on the documents being requested, the IRS and FinCEN also want to see that compliance is discussed and documented at board meetings as well — an area where I believe many smaller operations in the space are falling short.

KYC Is Key in Title 31 Evaluations

Deborah Connor, the principal deputy chief, asset forfeiture and money laundering for the Department of Justice (DOJ), addressed the casino industry with some insight into the Title 31 exams that have been prevalent in their industry. The most common findings in those Title 31 exams were that casinos failed to “know their customers” properly. Ms. Connor outlined the four critical (and minimum) components of an anti-money laundering (AML) program as

- Internal policies, procedures, and controls;

- A designated compliance officer;

- Ongoing AML training; and

- Independent auditing to test the effectiveness of the program.

In order for an AML program to be considered effective, it needs to be “risk based” and “tailored to the unique needs, risk profile, and structure of each institution.” I’m sure that was just what every casino owner in the room wanted to hear: Effectiveness is subjective, based on the DOJ’s conclusion of the risk level.

The DOJ’s Hallmarks for an Effective Compliance Program

Make Sure Everyone Is On Board

From top to bottom, an institution must ensure that its senior business managers provide strong, explicit, and visible support for its corporate compliance policies. The people who are responsible for compliance should have stature within the company.

There must be mechanisms to enforce compliance policies. Those include encouraging compliance and disciplining violations. The DOJ does not look favorably on situations in which low-level employees who may have engaged in misconduct are terminated, but the more senior people who either directed or deliberately turned a blind eye to the conduct suffer no consequences.

A financial institution should also inform third parties like vendors, agents or consultants about the company’s compliance policies and of the expectation that its partners will also take compliance seriously. This means more than including boilerplate language in a contract. It means taking action — including termination of a business relationship — if a partner demonstrates a lack of respect for laws and policies

Be Sure to Follow Up

An institution’s compliance policies should be clear and in writing. They should be easily understood by rank-and-file employees beyond the compliance department. That means that the policies must be translated into languages spoken in the countries in which the companies operate.

Nevertheless, when the DOJ’s Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering Section evaluates a company’s compliance policy during an investigation, they look at how the policy is implemented, not how it reads on paper. Make sure that your compliance team has adequate funding and access to necessary resources.

Snitches Do NOT Get Stitches

An institution should periodically review its policies and practices to keep them up to date with evolving risks and circumstances.

It is a good idea to reach out to law enforcement proactively, through SARS and the FinCEN hotline. They encourage financial institutions to address suspicious activity before they see it.

Fines

FinCEN does not maintain a strict matrix for assessing penalties. Rather, FinCEN weighs a number of factors and considerations when determining civil monetary penalties:

- The nature and seriousness of violations

- Knowledge and intent

- Remedial measures

- Financial condition of the financial institution or individual

- Payments and penalties related to other enforcement actions

Conclusion

While it’s hard to argue with the stated goal of catching terrorists, the BSA certainly adds significant costs to the companies required to comply. The currency transaction reporting threshold of $10,000 has never been adjusted for inflation since its enactment in 1970, yet prices have increased by 547 percent since then. As such, $10,000 in 1970 is equivalent to about $66,326 in 2019.

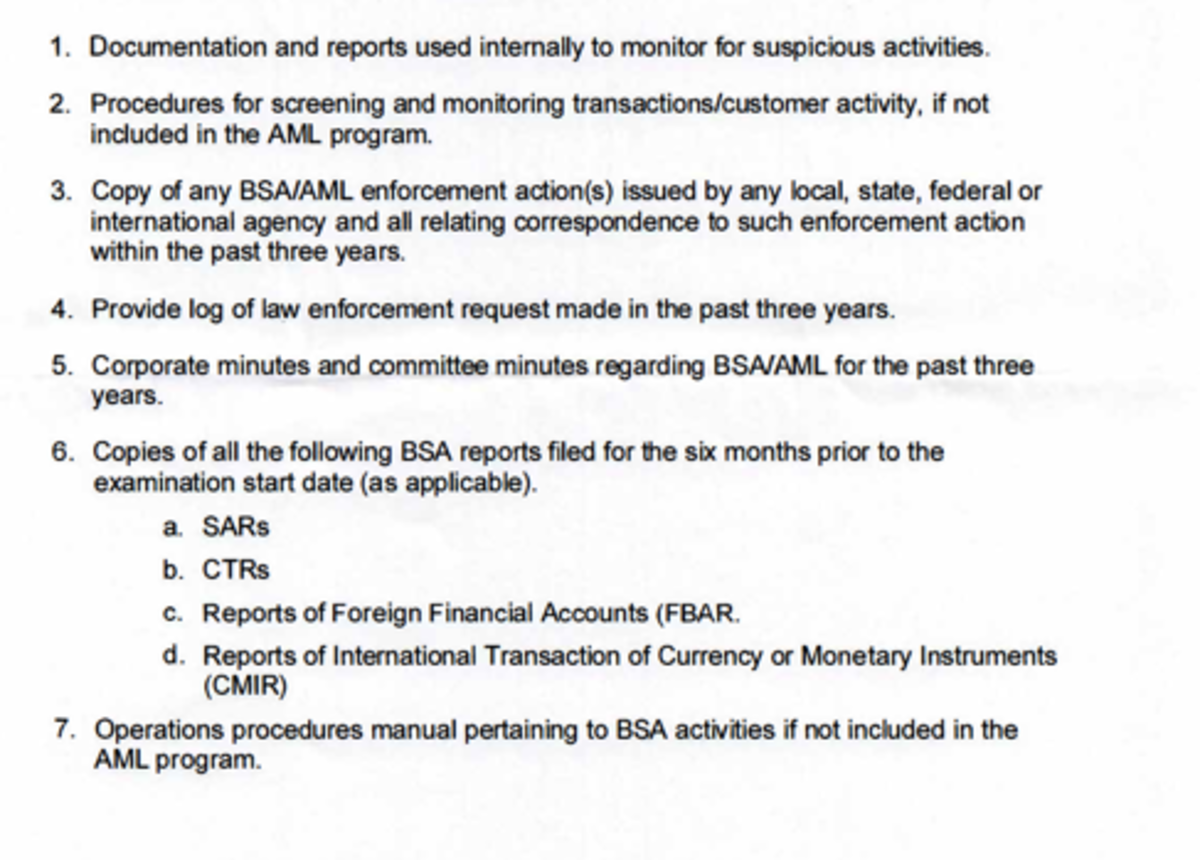

The costs of compliance seem to increase every year for companies involved in financial services, and there doesn’t appear to be any reform on the horizon. For example, even a solo bitcoin ATM operator who may process less than $10,000 worth of transactions in a month still needs to have 71 various documents ready for IRS review if they are selected for a Title 31 exam. I suspect these exams may lead to a consolidated bitcoin ATM industry, where only the larger players can afford the rising costs of compliance.

Further information can be found in these documents below:

This is an opinion piece by Sasha Hodder. It is for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal or tax advice. Businesses and individuals should perform their own due diligence and consult with experts before taking any actions. Opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of Bitcoin Magazine or BTC Inc.