Monetary Debasement

Debasement refers to the action or process of reducing the quality or value of something. In relation to money, it traditionally refers to the practice of reducing the precious metal content in coins while keeping their nominal value the same, thereby diluting the coin’s intrinsic worth. In a modern context, debasement has evolved to mean the reduction in the value or purchasing power of a currency — such as when central banks increase the supply of money, thereby lowering the nominal value of each unit.

Understanding Debasement

Before paper money, currency consisted of coins made of precious metals like gold and silver. Debasement was a common practice to save on precious metals and use them in a mix of lower-value metals instead.

This practice of mixing the precious metals with a lower-quality metal means authorities could create additional coins with the same face value, expanding the money supply for a fraction of the cost compared to coins with more gold and silver content.

Precious metals are no longer used for daily money exchanges and have been largely replaced by paper money, which goes through a process of debasement when the money supply increases. Debasement went through different processes and methods over time; therefore, we can define old and new methods.

Traditional method

Coin clipping, sweating and plugging were the most common types of debasement processes used until the introduction of paper money. Such methods were employed both by malicious actors that counterfeited coins and by authorities that increased the number of coins in circulation.

Sweating involves shaking coins vigorously in a bag until the edges of the coins come off and lay at the bottom of the bag. They were then collected to be used in the making of other coins.

Clipping would involve “shaving” the coins’ edges to remove some of the metal. As with sweating, the resulting clipped bits would be collected and used to make new counterfeit coins.

Plugging was a way of punching a hole out of the coin’s middle area with the rest of the coin hammered together to close the gap. It could also be sawn in half with a plug of metal extracted from the interior. The two halves would be fused again after filling the hole with a cheaper metal.

Modern-day methods

Money supply increase is the modern method used by governments to debase the currency. By printing more money, governments get more funds to spend but it results in inflation for its citizens. Currency can be debased by increasing the money supply, lowering interest rates or implementing other measures that encourage inflation; they’re all “good” ways of reducing the value of a currency.

Why is Money Debased?

Governments debase their currency so that they can spend without raising further taxes. Debasing money to fund wars was an effective way of increasing the money supply to engage in expensive conflicts without affecting people’s finances — or so it is believed.

Whether by traditional debasement or modern money printing, money supply increases have short-sighted benefits in boosting the economy. But in the long term it leads to inflation and financial crises, the effects of which are felt most acutely by those in society who do not own hard assets that might counter the loss in the currency’s value.

Currency debasement could also occur by malicious actors who introduce counterfeit coins to an economy, but the consequence of being caught can in some countries lead to a death sentence.

“Inflation is legal counterfeiting, Counterfeiting is illegal inflation.” - Robert Breedlove

Governments can take some measures to mitigate risks associated with money debasement and prevent unstable and weak economies, for example by controlling the money supply and interest rates within a specific range, managing spending and avoiding excessive borrowing.

Any economic reform that promotes productivity and attracts foreign investments helps maintain confidence in the currency and prevent money debasement.

Real-World Examples

The Roman Empire

The first example of currency debasement dates back to the Roman Empire under emperor Nero around 60 A.D. Nero reduced the silver content in the denarius coins from 100% to 90% during his tenure.

Emperor Vespasian and his son Titus had enormous expenditures via post-civil war reconstruction projects like the building of the Colosseum, compensation to the victims of the Vesuvius eruption and the Great Fire of Rome in 64 A.D. The chosen means to survive the financial crisis was to reduce the silver content of the “denarius” from 94% to 90%.

Titus’ brother and successor, Domitian, saw enough value in “hard money” and the stability of a credible money supply that he increased the silver content of the denarius back to 98% — a decision he had to revert when another war broke out, and inflation was looming again across the empire.

This process gradually continued to the point that the silver content measured just 5% in the following centuries. The Empire began to experience severe financial crises and inflation as the money continued to be devalued — particularly during the 3rd century A.D., which is sometimes referred to as the “Crisis of the Third Century.” During this period, spanning from about A.D. 235 to A.D. 284, Romans demanded higher wages and an increase in the price of the goods they were selling to face currency depreciation. The era was marked by political instability, external pressures from barbarian invasions and internal issues such as economic decline and plague.

It was only when Emperor Diocletian and later Constantine took various measures, including introducing new coinage and implementing price controls, that the Roman economy began to stabilize. However, these events highlighted the vulnerabilities of the once-mighty Roman economic system.

Read More >> Hard To Soft Money: The Hyperinflation Of The Roman Empire

Ottoman Empire

During the Ottoman Empire, the Ottoman official monetary unit, the akçe, was a silver coin that went through consistent debasement from 0.85 grams contained in a coin in the 15th century down to 0.048 grams in the 19th century. The measure to lower the intrinsic value of the coinage was taken to make more coins and increase the money supply. New currencies, the kuruş in 1688 and then the lira in 1844, gradually replaced the original official akçe due to its continuous debasement.

Henry VIII

Under Henry VIII, England needed more money, so his chancellor started to debase the coins using cheaper metals like copper in the mix to make more coins for a more affordable cost. At the end of his reign, the silver content of the coins went down from 92.5% to only 25% as a way to make more money and fund the heavy military expenses the current European war was demanding.

Weimar Republic

During the Weimar Republic of the 1920s, the German government met its war and post-war financial obligations by printing more money. The measure reduced the mark’s value from around eight marks per dollar to 184. By 1922, the mark had depreciated to 7,350, eventually collapsing in a painful hyperinflation when it reached 4.2 trillion marks per USD.

History offers us poignant reminders of the perils of monetary expansion. These once-powerful empires all serve as cautionary tales for the modern fiat system. As these empires expanded their money supply, devaluing their currencies, they were, in many ways, like the proverbial lobster in boiling water. The temperature — or in this case, the rate of monetary debasement — increased so gradually that they failed to recognize the impending danger until it was too late. Just as a lobster doesn't appear to realize it’s being boiled alive if the water’s temperature rises slowly, these empires didn’t grasp the full extent of their economic vulnerabilities until their systems became untenable.

The gradual erosion of their monetary value was not just an economic issue; it was a symptom of deeper systemic problems, signaling the waning strength of once-mighty empires.

Debasement in the modern era

The dissolution of the Bretton Woods system in the 1970s marked a pivotal moment in global economic history. Established in the mid-20th century, the Bretton Woods system had loosely tethered major world currencies to the U.S. dollar, which itself was backed by gold, ensuring a degree of economic stability and predictability.

However, its dissolution effectively untethered money from its golden roots. This shift granted central bankers and politicians greater flexibility and discretion in monetary policy, allowing for more aggressive interventions in economies. While this newfound freedom offered tools to address short-term economic challenges, it also opened the door to misuse and a gradual weakening of the economy.

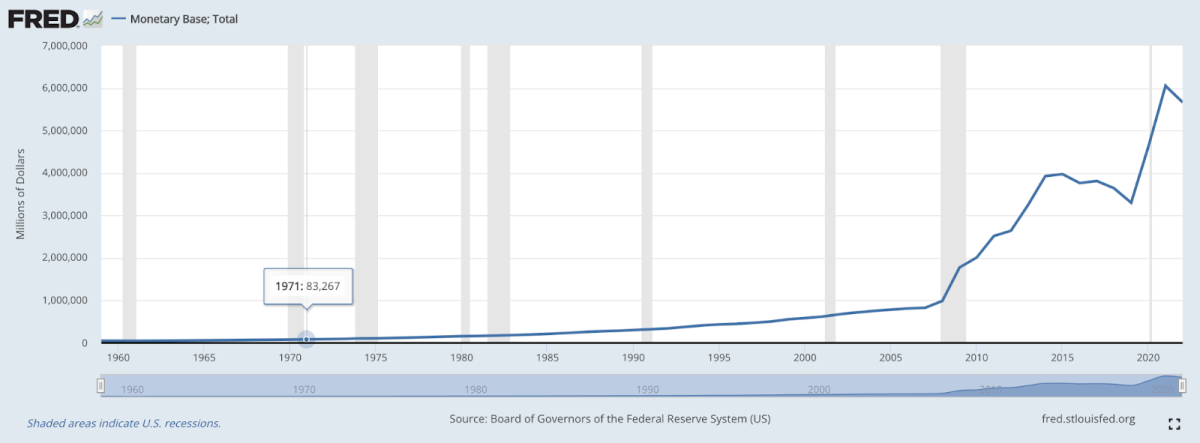

In the wake of this monumental change, the US has experienced significant alterations in its monetary policy and money supply. By 2023, the monetary base had surged to 5.6 trillion dollars, representing an approximate 69-fold growth from its level of 81.2 billion dollars in 1971.

As we reflect on the modern era and the significant changes in U.S. monetary policy, it’s crucial to heed these historical lessons. Continuous debasement and unchecked monetary expansion can only go on for so long before the system reaches a breaking point.

Effects of Debasement

Currency debasement can have several significant effects on an economy, varying in magnitude depending on the extent of debasement and the underlying economic conditions.

Here are some of the most impactful consequences that currency debasement can generate over the long term.

- Higher inflation rates are the most immediate and impactful effects of currency debasement. As the currency’s value decreases, it takes more units to purchase the same goods and services, eroding the purchasing power of money.

- Central banks may respond to currency debasement and rising inflation by increasing interest rates, which can impact borrowing costs, business investments and consumer spending patterns.

- Currency debasement can deteriorate the value of savings held in the domestic currency. This is particularly detrimental to individuals with fixed-income assets, such as retirees who rely on pensions or interest income.

- A debased currency can make imports more expensive, potentially leading to higher costs for businesses and consumers reliant on foreign goods. However, it may also make exports more competitive internationally, as foreign buyers can purchase domestic goods at a lower price.

- Continuous currency debasement can undermine public confidence in the domestic currency and the government’s ability to manage the economy effectively. This loss of trust may further exacerbate economic instability and even hyperinflation.

Solution to Debasement

The solution to debasement lies in the reintroduction of sound money — money whose supply cannot be easily manipulated. While many nostalgically yearn for a return to the gold standard, which was arguably superior to contemporary systems, it is not the ultimate solution. The reason lies in the centralization of gold by central banks. Should we revert to a gold standard, history would likely repeat itself, leading to confiscation and the debasement of currencies once again. Put simply, if a currency can be debased, it will be debased.

Bitcoin offers a permanent solution to this issue. Its supply is capped at 21 million, a number that is hard-coded and safeguarded by proof-of-work mining and a decentralized network of nodes. Thanks to its decentralized nature, no single entity or government can control Bitcoin’s issuance or governance. Furthermore, its inherent scarcity makes it resilient to the inflationary pressures that are typically seen with traditional fiat currencies.

In times of economic uncertainty, or when central banks engage in extensive money printing, investors often turn to assets like gold and bitcoin for their store-of-value properties. As time progresses, there’s potential for people to recognize bitcoin not just as a store of value, but as the next evolution of money.