In certain corners of the crypto community, ‘Decentralized Autonomous Companies’ (DACs), or ‘Distributed Autonomous Organisations’ (DAOs) are all the rage. In the same way that Bitcoin is decentralizing money, DACs seem to offer the potential to decentralize the entire world of business, commerce, finance, and the economy. They are businesses that can potentially be owned and run by their customers and their ’employees’, with no single owner, and, like Bitcoin, no central authority to act as a board of directors. They are, to some people, a big step on the road to greater freedom and autonomy in our own working lives and an antidote to the corruption and crony capitalism of our current corporate world, and the dehumanising influence that corporate hierarchies can have on regular working people.

Ideas like these have created quite a bit of discussion and excitement. Various ‘Bitcoin 2.0′ projects now claim to have developed or to be working on ways for people to create DACs, and the Bitshares project even claims to have started launching them.

But what does a DAC actually look like? How do they actually differ materially from traditional companies – and could any business become a DAC? Even amongst enthusiasts, many people still have no clear idea what the answers to these questions are, partly because until we decide exactly how we want to define what a DAC is, there is no exact definition. Exploring exactly what it is that makes a business a DAC is, I think, an interesting exercise which can simultaneously serve as an exploration of the limits of what a company like this is capable of doing. In order to do that, let’s take each word and its definition in turn:

Distributed:

A regular corporation has its ownership, whether it is private or in the form of shares, registered with a central government authority. It has a head office where a central board of directors gets together in the same physical location to run the company. The organisation of the business is hierarchical, and ultimately there is one individual, the CEO, who has authority over all decision making.

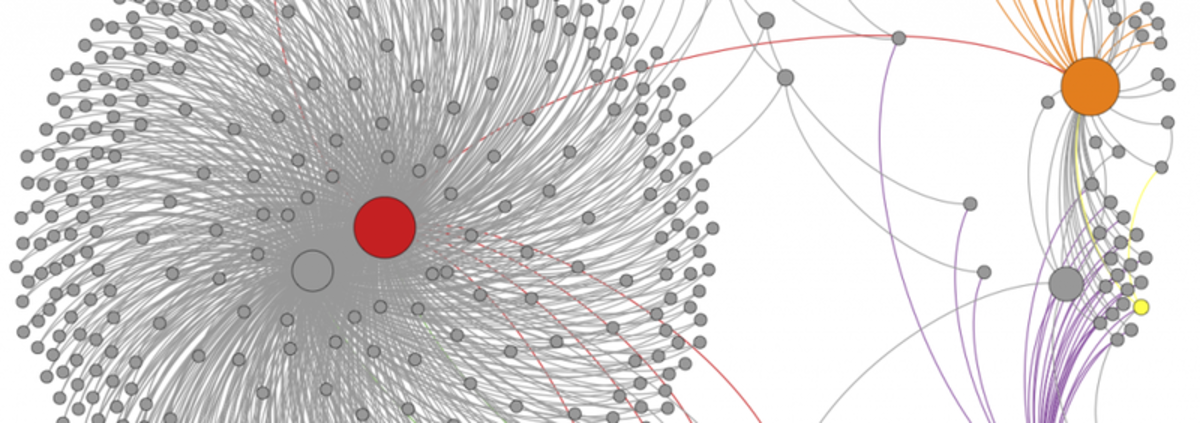

It is generally assumed that a DAC, on the other hand, has its ownership verified by a block chain or other P2P public ledger. This block chain is ‘distributed’ just as Bitcoin is, because it is run by a large number of peers, none of which has a privileged position over the others. Beyond this, however, it is also generally assumed that decision making power and even the work done to produce the company’s product or service is also ‘distributed’, meaning that it is spread out across a large number of peers, each of whom has equal authority. If this is the case (it may not necessarily be so) then the fundamental structure of a business like this is egalitarian and co-operative rather than hierarchical – and this probably the biggest difference between a DAC and a regular business.

Autonomous:

There really is no single vision of what a DAC looks like, and this comes out the most when you consider what is actually ‘autonomous’ about it. Currently there are two main competing visions, represented by the two biggest projects to have set out to create an infrastructure and protocol for the creation of digital autonomous companies or organisations: Ethereum and Bitshares.

Ethereum was the project which first introduced me to the concept of DACs and DAOs, and whilst the emphasis of its development team seems to have shifted more towards apps and ‘web 3.0′ technology, these things are still likely to be a big part of what Ethereum’s Turing Complete scripting language will enable. At its heart Ethereum is a ‘smart contract’ system, and any DAO created on this protocol is likely to be composed of an interlocking web of contracts automatically executing to perform specific functions. In this sense an Ethereum DAO would be autonomous in that it could run independently of human intervention. It could trigger payments to pay for its own hosting, run code to provide a service, and perform any other required functions completely on its own. It would not only be completely ‘autonomous,’ but potentially also completely ‘automated.’

On the other side of the coin are projects like those created with the Bitshares ‘tool-kit,’ in which a ‘Delegated Proof of Stake’ (DPoS) system is used, which means that coin holders vote for 100 ‘delegates’ who are allowed to earn revenue for running the nodes which maintain the network. The analogy of these people as the ‘board of directors’ of the business is sometimes used, as the ‘shareholders’ who own coins are encouraged to vote for people who work to make the business successful. Through this method the DAC effectively has employees, hired by the crowd.

The hiring of human employees blurs the line of what is ‘autonomous’ within such an organisation – the business is no longer a self-contained piece of software, although this may still be the core of the business, but instead pays people and presumably relies on them, at least in part, for its success. Individual ‘delegates,’ however, do remain autonomous. Each person hired by the DAC works independently, and there is no hierarchical structure.

The Advantages and Limitations of a Pure DAC

The first of the two systems described above, in which an organisation is structured entirely as a software entity independent of any human guidance or control, can perhaps be thought of as the most pure conception of a DAC.

There are some obvious advantages to having a company structured like this. It would, of course, be impervious to any kind of human corruption, greed, and frailty. When dealing with a company like this, as an investor, partner, or customer, you would know exactly what you are going to get – you would not need to trust them to behave well and you would not need to worry about human error messing things up. An organisation like this would also be able to operate effectively whilst making little or no profit, because software only needs the cost of its hosting to ‘live off’ and doesn’t get greedy for more.

But of course there are some equally obvious disadvantages, as you also consign human flexibility, creativity, understanding and compassion to the dustbin. As things stand there is a very limited number of things that can be accomplished by software working autonomously of human control. As Tom Ding, chief philosopher at Decentralized App crowd-funding specialists Koinify explains in ‘2020: A Call for DApps and DAOs,’ an organisation like this is ideally suited to performing work composed of small, simple and repetitive tasks in which “each task within the network can be easily divided, with the result of work being verifiable either programmatically or through human input; which is very hard to manipulate.”

Currently it is very difficult to see how any large or complex organisation could have all of its functions defined precisely and completely enough to be structured like this – and if it did, then having its operations ‘set in stone’ would make it inflexible and unable to adapt to a changing business environment. Over time one could imagine a situation in which an interconnected web of smart contracts develops, in which various ‘organisations’ and ‘companies’ may be built up from the same sea of source contracts and may reach reasonable levels of complexity. One could also imagine an organisation like this using contracts to hire human beings to perform tasks a machine cannot do on their own, but this is so far away from our current position it is difficult to envision with any clarity. If such a thing were to happen it seems to me that it would be something that would build up organically over time, with people focussing on building the contracts rather than the DACs, but with these contracts working together with each other in organisational structures which could only loosely be called a ‘company.’ Various contracts, each with their own set of relatively simple rules, may come together for a while into what may appear to be a ‘business,’ before dissolving their relationships to form new structures with new partners as they adapt to changing times. For the moment, however, there are very few areas of business simple enough to be conducted in this way, and very few ‘smart contracts’ operating out there in the wild.

Maximum Fuzziness and the DACification of the Corporation

The second class of DAC described above, in which a group of ’employees’ or ‘directors’ is elected via the block chain, has its own unique advantages and disadvantages.

By creating a role for actual human beings you allow human characteristics like creativity and flexibility to play their part in the success of the business. But each human being is still working individually – autonomously – in the way that they see fit. Of course a co-operative approach between ’employees,’ in which each one is free to do as they see fit but they still work together to build the business, is still possible; but it is easy to argue that this co-operative approach will inevitably be less efficient and more fragile than a traditional business, as there will always be times when people are pulling in opposing directions, or where a lack of support across the business would cause a good initiative to fizzle.

This kind of organisation seems as if it works best where there is a core product which can be completed even before the launch of the business, but in which the success of the business is dependent on a surrounding ecosystem of services or promotional initiatives. This is what we are seeing so far with Bitshares, in which the core product – each of the DACS that’s been launched so far – is a block chain with a relatively small and well defined set of key innovations funded through a pre-sale of coins or tokens. The Bitshares X banking DAC, for example, introduces assets such as BitUSD pegged to the value of external currencies and assets. Beyond publishing price feeds for these assets, which is a relatively trivial and a purely technical task which will not change over the years, the ‘delegates,’ or employees of this business, are not expected to maintain or develop this core business. Instead they are expected to build services and businesses which accept its digital currencies and assets like BitUSD, to promote its banking features to new users, or to support the current community of users in some way.

A DAC built like this is perhaps a little less ‘pure’ than one which doesn’t need human employees, and in return perhaps is a little bit more flexible and capable of a wider range of business activities, but it is still clearly very limited compared to a regular business. One interesting question to ask, however, is how many ‘impurities’ can you introduce before a company ceases to be a DAC?

For example, there is no technical reason why a business built with something like the Bitshares tool-kit could not have different classes of delegate: each might have a different probability of finding a block (and hence a different level of earnings). Perhaps these classes could relate to a marketing department, product development department, and so on. If you push this principle even further you could imagine a wide range of different employees being directly elected by shareholders – or you could just as well imagine a human resources department being voted in to hire other employees. Likewise you can imagine the core block chain being pushed into the back-room; imagine a physical shop, for example, with a Point of Sale system which allows the cashier to accept a $10 cash payment and automatically buy $10 of the company’s token on the open market and use it to purchase a product. The block chain now goes from the core service to a piece of back-end accounting software.

The specific advantages of doing something like this are entirely dependent on the specifics of the implementation. Whether a business like a big chain store implementing things like this would still qualify as a DAC or not is largely a matter of our own personal choice. But it may be that in the future the seemingly stark line between a DAC and a traditional business is a whole lot fuzzier than what we see at the moment, and that a wide range of businesses may be amenable to some form of ‘DACification.’